Some of Ireland's cleanest rivers and streams at risk from Coillte forestry

Environmental activists are concerned the State company’s cutting and replanting activity on peat is a ‘perfect storm for water quality impacts’.

THE PLANTING OF non-native trees in peat areas is putting Ireland’s pristine waters at risk.

In a new investigation, WASTED WETLANDS, Noteworthy found that Coillte plantations in the Wicklow Mountains are particularly concerning because of their proximity to water bodies already deemed ‘at risk’.

Environmentalists allege that Coillte’s policy of planting primarily non-native conifers on peat soil, which are then clearfelled, causes large amounts of acidic soil to be washed into water bodies which severely impacts on water quality.

Clearfelling is the chopping down of an entire plantation for commercial purposes in a short period of time.

In 2018, over 17% of Ireland’s water bodies were considered pristine or near-pristine, beaten out by only Austria (20%). Our closest neighbours in the UK had only 3%. However, today these waters are under significant risk.

The Draft River Basin Management Plan 2022-2027 identified over 200 sites under pressure from forestry across the country, but environmentalists are especially concerned about the Wicklow plantations on account of the location on deep peat and proximity to high-status water bodies.

A part of the Local Authorities Water Programme’s (Lawpro) ‘Waters of Life’ project – of which Coillte is a partner – involved selecting test catchments. One of these encompasses the rivers and streams that flow into Lough Dan, a scenic boomerang-shaped lake in a sparsely populated area of the Wicklow Mountains.

This is part of the catchment area of the Avonmore River. It was of ‘high’ ecological status 15 years ago and in recent years declined to ‘good’.

It is of significant risk of further decline, according to activists including representatives of Friends of the Irish Environment and the Irish Environmental Network, due to coniferous forests marked for clearfelling in the next two years.

Coillte said that it fully complies with required controls and guidelines in its forestry operations. These “are purposefully designed to ensure the protection of waters from forest operations”, a spokesperson said.

For this series, Noteworthy examined the State’s failure to tackle commercial exploitation of Ireland’s wetlands despite EU commitments to restore them as a key weapon in battling the dual climate and biodiversity crisis.

Forestry, and clearfelling in particular, was identified as a significant pressure to the water body at Lough Dan in a scientist-led study last year.

The water bodies around Lough Dan in Co Wicklow are at risk of further decline.

The water bodies around Lough Dan in Co Wicklow are at risk of further decline.

Noteworthy, the crowdfunded community-led investigative platform from The Journal, supports independent and impactful public interest journalism.

Risk of not meeting EU targets

Activists told our investigation team that the practice of clearfelling puts Ireland at risk of not meeting its requirements under the EU’s Water Framework Directive (WFD).

The WFD requires all European member states to bring the quality of their water bodies up to either ‘high’ (unpolluted) or ‘good’ status, and to improve those that have deteriorated from ‘high’ to ‘good’.

Waters of Life told Noteworthy that it recognises the risk of the river not reaching its targets under the WFD, and that forestry is a significant pressure.

However, a spokesperson said that the project has developed a “framework of measures document, with an associated forestry-specific annex”. These will form part of the project’s “approach to dealing with potential pressures associated with forestry”.

The rivers in the Avonmore catchment are designated as “blue dot” sites – water bodies that have the objective to maintain or recover their “high status” under the WFD.

The European Commission recently referred Ireland to the European Court of Justice over the state’s failure to halt industrial peat extraction.

When asked by Noteworthy if it had similar concerns over Coillte’s practice of planting on peat, a spokesperson for the Commission said that afforestation and clearfelling of forestry plantations on peat bogs can be “problematic for water quality and the ecological status of the aquatic ecosystem”.

In response to our queries, a Coillte spokesperson said that “harvesting and planting of trees is governed through a licensing process” overseen by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM). They continued:

“Central to this licensing process is a detailed environmental assessment carried out by ecologists to ensure the planned operation will not pose a significant risk and that effective controls are in place.”

They also said that Coillte fully complies with Forest and Water Guidelines. These include actions such as the establishment of buffer zones around the banks of rivers and other water bodies where chemicals or organic fertilisers are not used.

Coillte has a large number of plantations in the Wicklow Mountains.

Coillte has a large number of plantations in the Wicklow Mountains.

Viability of forestry on peatland criticised

Noteworthy visited the Avonmore site and observed a high number of areas of forest that had been designated for clearfelling, as well as a number of new plantations. The majority of these were on peat soil.

The viability of planting forestry on peatland – especially non-native conifers which make up the majority of Coillte’s inventory – has been criticised by experts for some time.

A 2016 study by Irish university researchers for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determined that forestry – especially non-native conifer plantations – is hugely damaging to peat soils.

It recommended the “cessation of conifer afforestation on peat soils in acid-sensitive headwater catchments”. The experts also stated that rehabilitation of peat be trialed instead of reforestation.

According to Ashley Glover from community group Rewild Wicklow, once these sites are clearfelled, they will simply be replanted, mainly with non-native conifers. While there is a replanting obligation on Coillte’s part under the Forestry Act, 2014, he said that this is not “nearly as set in stone as they make it out to be”.

“There’s a lot of misconceptions around the replanting obligation. The assumption is that the obligation is to basically re-do what was already there.” He said:

There’s no obligation to plant in the same place, to plant the same species or to plant with the intention to clearfell.

“There are a lot of different options and they could plant in a much more sustainable fashion.”

He added that “all that’s really required to get the obligation rescinded is a letter from the Minister, which has been done in the past“.

The Forestry Act, 2014 gives allows the Minister to “at any time vary conditions to any license granted”.

According to records released to the Irish River Project in 2021 under Access to Information on the Environment regulations, this discretion was exercised in relation to approximately 200 felling licenses around the country.

One such license in Tipperary saw the species of tree required by the license varied from Douglas fir to “Sitka spruce with 5% broadleaves”.

The legal basis of Coillte’s operations are currently the subject of a private members’ bill in the Seanad from Senator Alice-Mary Higgins.

Speaking on the bill last year, Higgins pointed out that Coillte’s mandate is purely on a commercial basis, with no obligations towards biodiversity. This bill seeks to give a mandate on climate and biodiversity to Coillte.

“It will place biodiversity and climate action centre stage in all the lands, soils and waters that are managed,” she said.

Minister of State Pippa Hackett, who has responsibility for Coillte, pointed out in response that it manages approximately 90,000 hectares of land “primarily for biodiversity” at present.

Neil Foulkes is concerned about the number of failed plantations on deep peat.

Neil Foulkes is concerned about the number of failed plantations on deep peat.

An issue with such peatland sites which makes Coillte’s decision to replant hard to understand for many environmental groups is the apparent low-yield of the forestry on them – and in some cases failed plantations.

Neil Foulkes, from Friends of the Irish Environment, said that Coillte won’t release yield data but that mapping data suggests “a lot of failed plantations, and a lot of these are situated on deep peat”.

Coillte maintains that there is a place for forestry on deep peat, though it clarified that it does not plant new plantations on peat, just replanted forestry that has been felled.

Replanting “is the most appropriate approach” in “productive peatland forests”, a Coillte spokesperson added, saying carbon absorbed by “the growing forest” compensates for “carbon emitted” from soil. They also said that wood produced could be used as a substitute for carbon and steel in construction.

In their 2022 financial report, Coillte reported that growth in the construction sector in the first half of the year contributed to an annual revenue of €479 million. €27.7 million was paid in dividends to the State as a result and €86 million was spent in capital investment.

Where peat forests have low-productivity with a high risk of carbon emissions, rewetting to restore the peatland is the appropriate approach, followed by rewilding where rewetting is not possible.

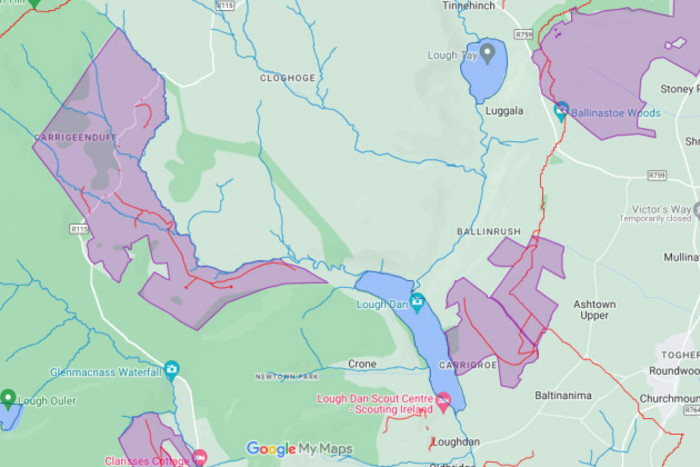

Map of the Avonmore catchment, with clearfelling sites marked in purple.

Map of the Avonmore catchment, with clearfelling sites marked in purple.

Draining a ‘huge threat’ to water quality

Forestry on peat can fail for a number of reasons, according to Foulkes.

“The most likely issue is access. Trees are planted in a location that was accessible at the time, but when they came back to harvest that had changed.”

The trees are just left as “it’s simply not seen as commercially viable to go to the expense needed to harvest plantations that you can’t readily access with heavy machinery”.

Even accessible trees “simply don’t grow properly on peat but the area still has to be drained”, he added. “This is constantly releasing carbon into the atmosphere as the peat degrades, whether or not the trees are performing well or not.”

This is a view also held by Glover.

“Drainage costs more than the eventual yield, and so the area is eventually just left to reflood. The sites and the trees then just become waterlogged, and the trees die standing up.”

The drainage necessary for the plantations, and the resulting washing of peat soil into water bodies is something that Fintan Kelly from the Irish Environment Network (IEN) says is a huge threat to water quality. He said:

Coillte’s clearfelling model on deep peat is a perfect storm for water quality impacts.

“The River Basin Management Plan identified forestry as the biggest pressure on high status water bodies,” he added.

The latest version of this government plan, which covers 2022 to 2027, aims to halt and reverse the deterioration in the quality of Ireland’s waters.

“There’s really no argument to be made for commercial forestry on deep peat, as it’s not even really sustainable,” added Kelly.

Continuous drainage results in plantations “not being commercially viable”, he said.

“Adding to this, they don’t succeed because deep peat is not a good soil for non-native conifers, so the argument for the carbon release form the peat being mitigated by the forestry simply doesen’t hold water.”

Being “loss making” has led Coillte “to look at other avenues to recoup their investment”, Kelly said. This includes selling land to develop “wind farms on sites that have been degraded by Sitka spruce”.

But “wind farms on peat bring with them a whole host of other issues, not least for water quality”.

Coillte’s sale of its land is set to be reviewed by the Department of Agriculture in 2024.

Our team asked Coillte about the development of wind farms on cleared sites, but no response was received before publication.

Clearfelled and replanted forestry in the Wicklow Mountains.

Clearfelled and replanted forestry in the Wicklow Mountains.

Owner of most peatland in Ireland

Despite these concerns, the fact remains that a substantial amount of Ireland’s forestry is currently planted on Coillte-managed peatland.

A 2022 submission by Environmental Pillar – a network of Irish environmentalist NGOs – pointed out the scale of Coillte’s holdings:

“Coillte owns 232,500 hectares of peatlands, making them the largest owner of peatland habitats in Ireland.

Tens of thousands of hectares of rare raised bog and blanket bog habitats have been drained and afforested in past decades.

Environmental Pillar argued that Coillte had an obligation to use its “significant expertise when it comes to habitat restoration” and should “play a leading role in acting on biodiversity loss and climate change”.

Without this change, activists fear that sensitive sites such as those in the Wicklow Mountains will be degraded beyond repair.

When asked about this obligation by Noteworthy, a spokeperson said: “Coillte has identified 30,000 hectares of peatland forest to be restored, and it is expected that a considerable percentage of this area will be rewetted, with other areas being rewilded.”

Rewild Wicklow’s Glover said that the most pressing issue is to embrace more sustainable forestry models.

One of these is continuous cover forestry, a form of forestry management which Teagasc says “relies on harnessing natural forest processes such as natural regeneration of trees, mixed species, increased biodiversity and natural forest development”.

“The first step is to break the cycle of clearfelling and replanting. Following that, we’d need some sort of triage to look at the worst sites,” he said. However, he added that the approach in upland areas will have to be to rehabilitate bogs, rather than continuing to plant trees.

A move towards continuous cover forestry would not be a new departure for Coillte. In 2020, Coillte Nature - Coillte’s biodiversity arm – committed to change how over 900 hectares in the Dublin Mountains was managed, moving away from the clearfelling and replanting model.

IEN’s Kelly also told Noteworthy that there should be a move away from afforestation and reforestation on peatlands, and towards rehabilitation and more sustainable forest cover.

“Ireland needs to change the way that it deals with peat. While Ireland’s forestry sector is very resistant to change, we need to be restoring peat, rather than planting on it.”

—

Read more articles in this series >>

Are renewables on peatlands causing more harm than good?

By Steven Fox for Noteworthy

This investigation was proposed and part-funded by our readers. It was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe as part of a cross-border project with: Maria Delaney (Editor, Ireland); Swantje Furtak and Guillaume Amouret (Germany); Elisabetta Tola, Giulia Bonelli and Benedetta Pagni (Italy).

Noteworthy is the crowdfunded investigative journalism platform of The Journal.

What’s next We want to investigate who is financing Ireland’s offshore wind farms. Help fund this work >>