‘Shouting into a black hole’: Chronic delays to autism services failing children

Families left in limbo as hundreds of vacancies in HSE teams impact capacity to provide autism support.

—

“NOBODY IS TREATING this like the house is on fire.”

This is how 12-year-old Cara Darmody recently addressed the Oireachtas Committee on Autism, not holding back in her disgust at how her two autistic brothers Neil and John – both non-verbal and in need of constant care – have been “treated disgracefully” by the State.

Alongside her father Mark, Cara is a vocal campaigner, raising awareness through multiple campaigns, speaking at events and meeting some of Ireland’s most senior statespeople.

Despite the pride that his daughter’s campaigning brings, Mark told Noteworthy his family’s attempts to access services for the boys is “horrific, humiliating and inhumane”, with big impacts on their development, especially Neil.

Neil, now 10, was first identified as autistic in 2016. He also has a mild to moderate intellectual disability, but this was not diagnosed until 2018 when he was assessed as part of the entry process for a school that could assist with his needs.

However, it was clear to Mark that his son’s intellectual disability was “far worse” than this assessment determined. It was found in 2020 that Neil needed to be reassessed as a priority as he was deemed to be in the severe range of intellectual disability.

Neil is still waiting for a full reassessment, all the while his quality of life is getting worse – hitting his own head and biting his hands every day. “Due to total incompetence, we have lost almost three years,” Mark told us. “This family is being effectively ignored as if we do not exist.”

Cara with her parents Noelle and Mark at their home in Co Tipperary

Cara with her parents Noelle and Mark at their home in Co Tipperary

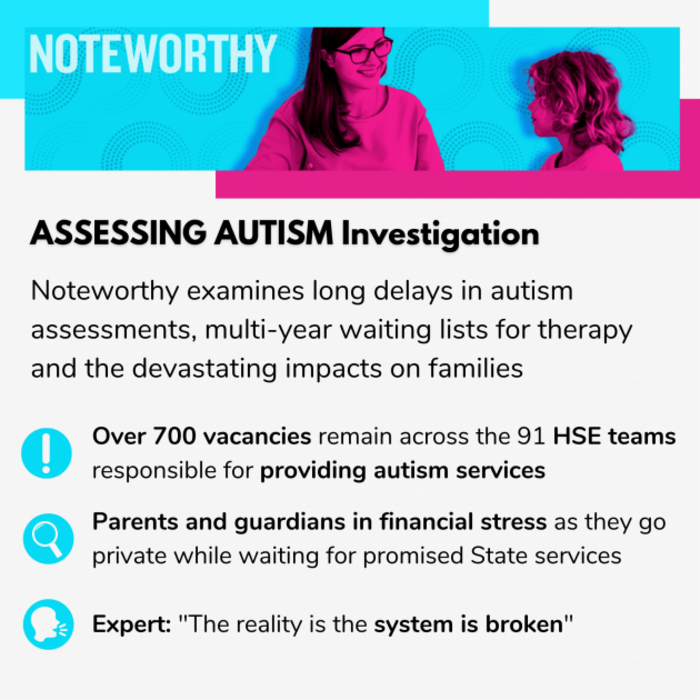

The Darmody family is not alone. Over the past month, as part of our ASSESSING AUTISM investigation, more than a dozen families told us about their ongoing struggles to ensure their autistic children, living in the shadow of a dysfunctional State service, receive timely assessments and subsequent services. We found:

- Children waiting years for assessments, leading to developmental delays as well as lack of access to vital educational supports and school places

- Families left in limbo post-diagnosis, facing multi-year waiting lists for therapy and other supports

- Parents and guardians in financial stress as they go private while waiting for promised State services

- Over 700 vacancies across the 91 teams responsible for providing autism services, with the HSE stating that lack of qualified staff is “impacting our capacity to deliver services”

- A lack of joined-up thinking and incoherent data collection across HSE teams that autism experts and Disability Minister Anne Rabbitte say make it difficult to know where to best direct resources

You can also explore the key issues by listening to The Explainer x Noteworthy podcast on this project:

—

Delays and inconsistent services

The Department of Education estimates that autistic people make up around 1.5% of the population. However, in reality, this figure is likely much higher, and future estimates should reflect this as understanding of neurodiversity improves.

A 2022 study, for example, found that almost 5% of the school population in Northern Ireland is autistic, with experts who spoke to our team clear that Ireland’s figures are lower, in large part, due to lack of early assessment.

There was no clear consensus on the definition of autism from either autistic people or healthcare professionals who diagnose autism that spoke to Noteworthy. This most likely reflects the diversity of autism itself.

However, most did say that autistic people process sensory input, communication and social interaction in a different way to a more neurotypical person, which can cause issues such as sensory overload, anxiety and emotional overstimulation.

- Noteworthy, the crowdfunded community-led investigative platform from The Journal, supports independent and impactful public interest journalism.

There are various channels available for assessment. The most heavily signposted by the HSE is the primary care-route: getting a referral from a GP or public health nurse which is then screened and processed by one of the 91 Children’s Disability Network Team (CDNTs) across the country.

CDNTs provide specialised support for children with complex needs, including occupational therapy, psychology, physiotherapy as well as speech and language therapy.

Waiting times for a formal diagnostic assessment are lengthy, however, with the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Autism recently hearing from witnesses in over a dozen public sessions who outlined a litany of concerns over delays in assessments, with services lacking or inconsistent standards in service delivery.

‘Early intervention is vitally important’

This is exactly what happened to Mary’s* son, Noah*, who from an early age had problems with emotional self-regulation, communication and sensory overload that caused him to get upset and lash out, including self harm. “He can get quite violent and aggressive when he can’t self-regulate.”

Mary and her partner sought help when Noah was two but did not receive a diagnosis until he was five, and already in junior infants.

She said that they had to jump through many hurdles along the “cumbersome process”. This involved waiting four months before an initial online session with a trainee psychologist who determined, with no physical observation, that such behaviours are just common for his age.

“When he went to creche, the behaviour started coming out again even worse,” Mary said. Yet, when she tried to get another psychologist appointment, Noah was put back on another waiting list for months.

He was then observed in person and referred to an Early Intervention Team. This is when the “whole wait started” over again, and Noah only received his assessment a year and a half later in October 2022. This was followed by his official diagnosis in November.

Mary is happy to finally have the diagnosis from which she hopes Noah gets specialised support. It also helps her family to respond better to his needs. “We know he’s not having a tantrum. No, this is autism. So I need to be more supportive of him.”

However, she is still frustrated at what the long delay cost both her son and herself. “I didn’t understand why he was behaving this way. And it caused us a lot of stress,” she said. “It takes an emotional toll.”

Early intervention is fantastic “when you can get it,” according to Eleanor McSherry, head of autism studies at University College Cork (UCC). Her interest in autism stemmed from her autistic son, now in his twenties.

While not a prerequisite for a fulfilling life, McSherry said an early diagnosis can be life-changing for an autistic child, helping them to better understand who they are and how their brain works.

It can also help their families better understand their behaviour and needs, and importantly, give access to tailored services depending on need.

“I have seen the benefits of it because my son is strong in his identity. He’s a positive person. He’s a happy person within himself,” McSherry said. However, as the co-founder of the Special Needs Parents Association of Ireland, she has also seen children on “the other side” who don’t get help early on.

Children can then have issues with mental health, anxiety, suicide ideation, can be “terrified of school” or self harm, according to McSherry. She knows of children who required treatment in “mental health units at 15 and 16-years-old because they did not get the help and the care that they deserve. So early intervention is vitally important”.

McSherry, herself recently diagnosed as autistic, said she is proof that you can get through life without an official diagnosis. But this was not without its challenges.

“I know I have scars and I know plenty of people who have scars too” from going through most of their life without the understanding of their very own neurodiversity, she added.

‘Not delivering for families’

Adam Harris, CEO of AsIAm, says the current assessment model is “not delivering for families"

Adam Harris, CEO of AsIAm, says the current assessment model is “not delivering for families"

According to Adam Harris, the CEO of AsIAm, Ireland’s national autism charity, waiting extensive periods of time to access assessment is “a systemic problem encountered by just about any family that is going through the system”. AsIAm is led, directed and governed by autistic people.

“You’re talking about a multi-year wait for the vast majority of families,” said Harris. A 2021 AsIAm survey found that a staggering 42% of respondents were waiting more than two years for assessment. This, Harris said, makes it “very clear” the current model is “not delivering for families”.

Data released to our team by the HSE from the end of December shows that 9,650 children were also waiting over 12 months for their initial contact with a CDNT, with around 4,000 more waiting between six and 12 months. The HSE could not provide specific data for cases related to autism, so this data relates to all children waiting for contact with a service team.

These long delays have led many families to instead look for an Assessment of Need (AON) through the Disability Act. The HSE is legally obliged to arrange a referral for assessment within three months of receiving a valid AON application, and, if required, carry out a full assessment within a further three months. This should then be followed up with any additional services required.

Yet, despite the clear binding deadlines in the Act, there are also major delays in the AON process. A HSE spokesperson told Noteworthy that, at the end of 2022, there were over 4,600 AON applications overdue for completion, taking an average of 16.5 months to complete reports last year. Again, we requested data on autism cases specifically, but this was not provided to us by the HSE.

The spokesperson said that the Disability Act gives an individual the right to an assessment but “does not give the right to a specific assessment at a particular point in time”. Nor does it, they added, “give a right to access to a diagnosis unless it is required at that time to identify the health needs occasioned by the disability”.

‘Begging for help’

Clare* and Conor* found this out the hard way after they started noticing delays in their daughter’s development at nine months old. Like Mary, they first tried to go down the primary care route, only to be told by their public health nurse that they would need to wait until she was two for a referral from a community doctor.

“We spent nearly a year and a half twiddling our thumbs waiting [when] there were red flags there already,” Conor told us. Further delays led them to seek an AON, which took the family on an emotional and financial rollercoaster over the following years – with their daughter, Emma*, only receiving her diagnosis when she was six.

This included finding out that an administration error meant that Emma wasn’t referred for assessment. This only happened after months of “phone calls, letters and emails begging for help”, according to Clare. During this period, they organised for a private assessment at their own expense, which, following a protracted legal battle, was used by the HSE for completing the AON process.

“When she was two, they knew what was going to happen [with delays] because they see that every day,” said Conor. “That was four or five years for them to take care of something we had been saying when she was nine months old.”

Emma is still waiting to receive one-to-one therapies in line with the recommendations in her support needs file. “They’d always been dangling out this idea that once we get the AON, then the support will be there. But you get it and the support is not there,” Conor said. “It’s like shouting into a black hole.”

The same happened to Mary, who still doesn’t know if her son Noah will qualify for one-to-one therapy. While he does go to group therapy and a Lego club, she said there is no structure. “You just get an email saying ‘we’re running this’, ‘are you free’, or ‘do you want him to join?’ It’s like there’s no plan in place yet. It’s all up in the air,” she said.

Parents and guardians “really believe that this diagnosis is going to open doors, and put that focus on getting this piece of paper”, said Adam Harris of AsIAm, “but then it is slid across the desk and it’s ‘we might see in four or five years’.”

A major cause is the lack of available expertise in the CDNTs. In October 2022, none of the 91 teams were fully staffed, with over 700 vacancies. A HSE review stated that this lack of staff is “impacting our capacity to deliver services”, with an average vacancy rate of 34% across the teams.

“If you look at the number of vacancies, the reality is the system is broken,” said Harris. “We need to be training a lot more occupational therapists, psychologists and speech and language therapists, and that’s just not happening at the pace that it needs to happen.”

Another issue is a lack of standardised delivery and collation of data, according to Harris. This is needed to inform where resources should be best directed.

“Unfortunately, our experience with nearly everything related to autism in this country [is that] we’re data poor. When you’re data poor, it’s very hard to fix problems,” he said.

Organisations and families have called for an autism database for years. This was echoed in February, when the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child also called on Ireland to “strengthen the collection and analysis of data on children in disadvantaged situations including children with disabilities”.

‘Everything is paper-based’

Minister of State for Disability Anne Rabbitte has also faced difficulties in accessing information from the HSE. She told Noteworthy that the data issue is a key problem, as, at the minute “everything is paper-based” with “different ways of delivery” across the 91 CDNTs.

“I always said when I came into the role, the one thing that frustrated me most was getting different responses from different areas around the country and people working in vacuums.

“We should have live data within a month so we can see what the needs are on the ground, if there’s a change in demographics, how we can find the funding and the investments that need to go in behind it,” she said. “We need to see that, so we can start planning in advance, not this emergency, rapid response.”

A HSE spokesperson told us that a National Information Management System is in development to provide waiting list data. In the interim, manual collection is on-going and “will provide information to the local areas regarding the number of children waiting”. They did not provide a timeframe for when this system will be in place.

Debts of despair

In the meantime, families across the country often resort to private services as they wait for State support and can incur considerable expenses. Some, who spoke to Noteworthy, have also lost wages from leaving work in order to look after their children or take them to appointments.

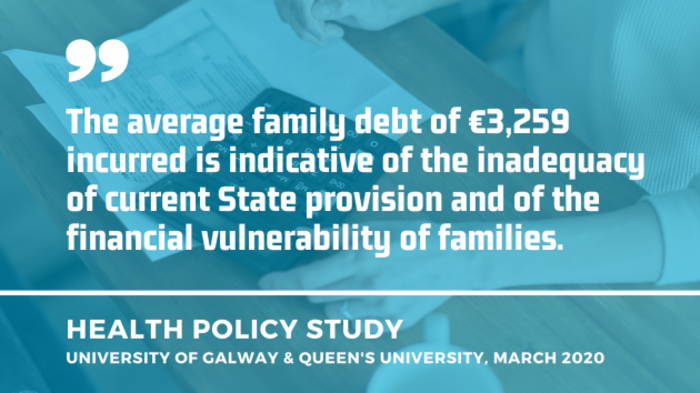

There have been a number of Irish studies which show just how much financial strain families are under.

A 2019 study found the average annual cost per child came to almost €28,500 for private services and lost income. By comparison, annual government expenditure per child on autism-related resources was just over €14,000. A further 2020 study found that families were accruing an average annual debt of €3,250, pointing to a “significant level” of economic hardship and financial vulnerability.

More recently, a 2021 report, commissioned by the government, found that the additional cost of disability for autism was almost €14,450 annually and families of autistic people who require care miss out on around €24,500 in annual income.

“You start to use whatever money is left to try to go privately and you cut out that small cup of coffee in a cafe, [buying] clothes or skip meals because every penny goes towards whatever we can provide,” Clare told us. “We have no joy, no timeout, because we need to pay for the minimum therapy that we can give to her.”

No diagnosis, no education support

Assessment delays also impact access to school places. While many autistic children can integrate well into mainstream classes, others require extra support.

“Very often the appropriate education for a child may be a special school or a special class and the only means by which you can get that is if that’s recommended in your diagnostic report,” according to AsIAm’s Harris.

Graham Manning, a post-primary autism class teacher in Co Cork, echoed this finding, telling us access to an autism class is not possible without diagnosis. “Unless it’s on black and white paper, you’re not accessing any support whatsoever.

“The earlier you get a diagnosis, the better it is for the person because all the supports are in place, the explanations are in place [and] every educator you’re going to meet is going to know you’re autistic. That itself is an advantage.”

Sinéad* – an “incredibly angry and exhausted” mother “at her wits’ end” – told us that her now-seven year old missed out on exactly this support when he started primary school due to delays with his assessment.

“He’s so clever and bright and sweet,” Sinéad said of her son, James*. He loves dinosaurs, science and drawing and is a very imaginative deep thinker who “can make surprising and insightful mental leaps and connections”, Sinéad added.

Yet, James also comes up against common emotional and sensory challenges faced by autistic people, with concerns first flagged during his 22-month development check in 2017. Sinéad said that the public health nurse told her that his speech and language were “way behind what would be expected for his age”.

Despite an early referral for therapy, James was on a waiting list for 10 months. He was then reviewed but only received support every four to six months over the two years that followed.

According to Sinéad, this was the only care he received, and there were no concerns raised as to autism, until he started playschool when he was 3.5-years-old. She then received “alarming feedback” that he could not handle the environment and was getting very distressed.

The school applied for support and an extra teacher was funded to work one-on-one with James. This created a “knowledgeable, flexible and nurturing environment” in which “he slowly started to blossom”, she said.

Up to this point, Sinéad said she was “clueless” about autism or neurodiversity, and that no one directed her to the AON process. “Only for a friend of mine happened to tell me about it I wouldn’t have had a clue”.

She submitted her AON file a year before James was due to start junior infants, expecting the process to be completed within six months. Sinéad had “hoped to have a special needs assistant [SNA] lined up to facilitate his needs”.

However, she was left in “complete limbo” as “deadline after deadline passed”, until the diagnosis was finally received that James was autistic with sensory processing difficulties.

This wasn’t until almost two years after her AON application. James had gone through an entire year of primary school without any support. He now has a place in an autism class in his mainstream school that Sinéad said has been “transformative for him”.

However, she said, this cannot undo the harm caused by the “disastrous” start to primary school by missing out on SNA support and a place in an autism class as he waited for a formal diagnosis.

“My son now has a lot of trauma from junior infants that continues to impact him, his mental health and his attitude to school – because the government refuses to provide my little boy with adequate help.”

‘We know where the problems are’

Even with a diagnosis in place, however, Manning told us school places are not guaranteed. There is a lack of autism classes nationally, as well as a need for training for teachers to gain the skills to support autistic children.

“We have [had] dozens of applications for the 16 years I’ve been doing this. Depending on the year, two, three or four [places] will be on average available, regardless of diagnosis, regardless of needs,” the autism teacher said.

This leaves many autistic students having to find another nearby school, with some travelling up to 40 minutes each way to get to school, Manning said.

According to the Office of the Children’s Ombudsman, around 15,500 autistic children are travelling outside of their locality each day. Many others are placed on short school days that can cause significant feelings of exclusion and anxiety.

For Eleanor McSherry, head of autism studies at UCC, there is little excuse anymore for the government as we are now two decades on since the Autism Taskforce. This group of top experts released its thorough 521-page strategy, compiled with input from autism organisations and family support groups.

“This is why it is so soul destroying that I am here, 22 years later, and very little has been done,” McSherry said. “We know where the problems are.

“It’s choosing to actually grasp the nettle and just make a commitment. It will cost us money in the short-term, but the long-term benefits to the whole community, and to the whole island, are just immeasurable.”

Minister Anne Rabbitte has plans for wide-ranging changes to the autism assessment process

Minister Anne Rabbitte has plans for wide-ranging changes to the autism assessment process

Disability Minister Anne Rabbitte told our team that she has a plan to turn the ship around with the Autism Innovation Strategy and also wants to see six regional assessment centres set up “first and foremost to clear that backlog”.

Within these centres, there would be liaison officers to ensure children are redeployed to CDNTs to receive “timely intervention”. She also wants to see teams expanded to include social carers, behavioural and art therapists, more support for equine therapy, and also family support.

“We need the whole gamut. It’s not just a medicalised model, we need that social piece of it as well, which is completely missing.”

Minister Rabbitte pointed to how the State can learn from, and work with, families and “experienced skilled staff” in autism organisations and clubs up and down the country, who she called “leaders in their own right”.

Reducing the backlog is her first priority, with additional funding provided in Budget 2023. The HSE is now contracting private consultants to work through overdue assessments. Last week, the Department of Health launched a Waiting List Action Plan setting out additional funding and priorities to address the backlog.

“We do know the quicker the intervention, the quicker the support, the quicker the understanding and the more relief for the child, but also for the family unit,” Minister Rabbitte said.

‘Just do your job’

While the Minister is saying the right things, UCC’s McSherry won’t be satisfied that meaningful change is coming without a serious shake-up at senior management level across the health service and at a departmental level.

“I’ve been through 10 ministers now, either in disabilities or education, who have shook my hand and are saying the right things. We’ve had three or four strategies [and] a couple of goes at an Autism Bill. So I’m sorry, I’m not really confident. I’ve been here before. I’ve been burned.”

McSherry is pinning her hopes on the “absolutely fantastic” autistic kids now going through education and university. “They will be the changers rather than who’s here now. They’re the people who I have confidence in.”

Many families share a similar hope, and there is a long journey ahead for many to build back up any level of trust that the State is now in their corner.

“For the new families on this journey, we are very sorry to say it but do not count on the public service at all,” said Clare, still waiting for key post-assessment support for her daughter Emma.

“We would encourage people to speak up, go to the media and protest to show how this system is broken and needs serious and responsible attention from authorities to change it urgently.”

Cara Darmody has the same fire in her belly as she continues to campaign for her two brothers and hold policymakers to account.

“It is surely not wrong of me to ask politicians and the HSE to just do your job.”

*Names have been changed

If you need to speak to someone, contact:

- AsIAm: 0818 234 234 (opening hours) or email support@asiam.ie

- Samaritans: 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.ie

—

FULL SERIES – OUT NOW

Have a listen to The Explainer x Noteworthy podcast on our findings

By Niall Sargent of Noteworthy

This investigation was proposed and funded by you, our readers, with support from the Noteworthy investigative fund. Noteworthy is the crowdfunded investigative journalism platform from The Journal.

Please support our work by submitting an idea, helping to fund a project or setting up a monthly contribution to our investigative fund HERE>>