On social welfare, unable to buy a house: The reality facing Ireland's academics

Analysis reveals an average of over 11,200 lecturers working in temporary and casual contracts.

“I’VE NEVER SETTLED down. You can end up not having a family. I don’t have pets – I foster – as you just don’t know if you’re going to be around or not.”

Dr Ingrid Holme, adjunct research fellow in sociology at UCD, has worked as a lecturer and researcher in universities across Ireland and the UK for more than the past decade. “There’s a turmoil to that constant movement and the lack of investment you can make in your own life,” she explained.

“I’m 45 and there’s no way I’m going to get a mortgage on a house. That’s not going to happen.”

In the course of a six-month investigation, Noteworthy has discovered that a significant proportion of academics and researchers working in third-level institutions in Ireland are suffering from instability of employment and short-term contracts are rife in the sector.

Holme’s current position is unpaid but allows her to use the facilities of the university. Her previous students often commented on her “lovely job”, she said, but they didn’t know she faced applying for jobseeker’s allowance at the end of her contract.

“You’re a lot more vulnerable to complaints and criticism. At the end of the day your colleagues have a permanent contract. They will be there next year and you won’t.”

Dr Ingrid Holme wants better recognition for academics on short-term contracts.

Dr Ingrid Holme wants better recognition for academics on short-term contracts.

Academia is not the first sector that comes to mind when poor pay and conditions are discussed. However, this highly skilled sector contains a wide range of insecure contracts with many workers Noteworthy spoke to relying on social welfare to supplement their income as lecturers or researchers.

This casual engagement of workers that is sustained over a long period is very problematic in the sector, according to Frank Jones, deputy general secretary of the Irish Federation of University Teachers (IFUT). “I’ve dealt with the public and private sector, multinationals, semi-State bodies… and I don’t see anything like this anywhere else.”

Over the course of the pandemic, the Government and public have looked to experts in higher level institutions (HEIs) for guidance and researchers for tests and treatments, but are these workers being properly treated?

As part of this investigation, Noteworthy has communicated with over 30 people who worked in temporary or short-term jobs in HEIs around Ireland. We also submitted freedom of information (FOI) requests to every university and IT across the country in order to get data on this issue. We can now reveal:

- Casual and fixed-term contracts are having a detrimental impact on workers’ finances and ability to plan their family or future.

- There has been an average of over 11,200 lecturers working on a temporary or casual basis in recent years across Irish universities and ITs, costing an average of over €67 million each year.

- Across Ireland, 440 academic staff in universities and ITs were in continuous employment in excess of two years but not on a CID (contract of indefinite duration), with UCD’s numbers increasing by almost 50% in recent years.

- There is no central record of complaints about employment status in a number of HEIs.

- People who spoke up about staffing issues received ‘pushback’ from colleagues for ‘letting the side down’.

Over the weekend, further parts of this investigation will explore how precarious work is having an impact on diversity in HEIs and delve into ongoing campaigns by postgraduate researchers for workers rights.

Staff numbers difficult to obtain

Insecure employment in HEIs is not a new issue and has been ongoing for many years, though almost all experts we spoke to said it has gotten significantly worse since the recession in 2008.

In an academic article published last year Dr Theresa O’Keefe and Dr Aline Courtois summed up the situation in Ireland for many higher education workers:

“Depleted state funding, rising student numbers and sector‐wide hiring freezes have normalised the reliance on temporary, short‐term labour, reinforcing the segmentation of academic labour.

“Many precarious workers are de facto excluded from career progression mechanisms and are likely to get stuck in a ‘hamster wheel of precarity’ with few chances of accessing secure work.”

There is also a gender divide with almost 60% of permanent full-time academic roles held by men. More women work in part-time temporary academic jobs with this gap increasing in recent years to 71% in universities and 63% in ITs in 2019. We explore this issue as well as others linked to diversity in the sector in part two of this investigation.

An expert group examined this issue and the Cush Report was subsequently published in 2016. It found that over 50% of the almost 13,000 lecturing staff across Irish universities and institutes of technology were either on a part-time or temporary contract. Over 4,500 – or 35% – of lecturers were on temporary contracts at the time.

This report concluded that “there is no doubt that that the use of part-time contracts is a necessary and desirable feature of third level education in Ireland”, but also added “that for many lecturing staff part-time contracts leave them in a very precarious position financially and reduces the attractiveness of lecturing as a career.”

One of the most precarious positions in HEIs is that of hourly paid staff who are normally not entitled to sick leave or maternity leave. According to O’Keefe’s article they are excluded from the unfair dismissal protection, not protected by the minimum wage act or the principle of equal pay for equal work and have little recourse for complaint under labour legislation. “In many cases, trade unions cannot do anything for them,” the article stated.

To get an up-to-date picture, Noteworthy asked every university and IT for data for each of the past three academic years on a number of different topics. The author of the 2016 report, senior counsel Michael Cush, said that “the gathering of relevant statistical data proved a difficult and time consuming task”.

We also found this to be the case, with some email threads we had with HEIs spanning over 30 emails and multiple reminders were needed over the course of a number of months. We persisted and over seven months after we initially sent the FOIs, we finally had responses back from all institutions, though some did not answer our requests fully.

- You can support the huge volume of additional work required over the past number of months because of these time-consuming FOI requests by supporting the Noteworthy general fund or giving the gift of investigative journalism to a loved one this Christmas.

For all FOI responses, since each institution replied at a different time, due to Covid-19 and other delays, different academic years were provided with some dating back to 2016/17 and others to 2017/18. Though they were asked in the FOI for data for the past three academic years, Trinity College and TU Dublin provided only 2019/20 figures.

Due to Covid-19 and other delays, different academic years were provided by HEIs, but an average of the data provided is summarised here.

Over 11,000 temporary or casual lecturers

To find out just how many temporary lecturers are employed, we asked HEIs to provide us with the total remuneration paid to non-permanent and/or casual lecturing staff employed for each of the past three academic years.

From the 17 out of 19 HEIs that answered this in full, the annual wage bill for casual and temporary lecturers amounted to €67 million, on average from the three years of data provided by most HEIs. This was spread across over 10,600 staff but this increases to over 11,200 staff when DCU – who didn’t give a wage figure – is added.

Even with one HEI missing, that is over double the number of temporary staff listed in the Cush report, though it is noted in that report that universities – with the exception of NUI Galway – did not include staff on hourly paid contracts in their figures. Though the data provided to Noteworthy is also not completely uniform across HEIs, many did include this category of staff.

Temporary Wages & Lecturer Numbers: We have created a searchable table which lists the full set of figures for all years provided to Noteworthy by the HEIs. Click here to explore (best on PC/laptop). A mobile-friendly summary is available here.

With the exceptions of significant increases in annual spend in Athlone IT – due to the “introduction of the Springboard programme” – and UCD, as well as decreases in IT Tralee, the spend on temporary staff has been fairly consistent in universities and ITs from year to year, within the four year period.

“That means there is work there that’s predictable and regular,” according to Aidan Kenny, assistant general secretary of the Teachers’ Union of Ireland who represent staff in ITs across Ireland and TU Dublin as well as secondary school teachers.

‘No option’ but to hire temporary staff

Almost 60% of the annual average wage bill for non-permanent and casual lecturers that we compiled was spent by UCD and Trinity College.

UCD paid the highest amount – over €19.6 million – of remuneration to 1,368 of this category of staff employed last year. Of these, 352 were paid through the hourly payment system.

The university’s wage bill for casual and non-permanent lecturers has grown €3 million over the past three years, though their level of staff has remained at a fairly consistent level.

A UCD spokesperson said that “UCD maintains the right to engage employees on a fixed-term basis for legitimate reasons” which in terms of academic staff included replacement of staff seconded to other roles, on a career break or taking research, maternity and parental leave.

It should be noted that the Employment Control Framework (currently under review) prohibited the university from filling non-core funded posts on a permanent basis.

The Government – through the Employment Control Framework (ECF) – placed a cap on the number of permanent staff that can be employed by each institution. A Delegated Sanction Agreement which will replace the ECF is currently being finalised.

One provision in the ECF meant that posts funded by sources other than the exchequer (Government) were only to be filled on a fixed-term basis. This was recommended to be deleted by the Cush Report four years ago.

Officials from the Department of Higher Education, the Higher Education Authority (HEA) and the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform are “currently engaged in discussions to agree revised principles for a new higher education staffing agreement to update the current ECF, which is implemented since 2011”, according to a spokesperson from the Department of Higher Education.

They added that the criteria of the existing ECF is still in place for HEIs. When asked about the Cush Report recommendation, the spokesperson said this “will be considered in the context of the development of the revised agreement”.

A spokesperson for the Irish Universities Association (IUA), who represent all universities in Ireland except TU Dublin, said, as a consequence of the ECF, “universities had no option but to hire staff under casual or temporary contracts in order to meet student demand”.

Michael Doherty, law professor and head of that department in NUI Maynooth said that there’s “a bit of a contradiction in terms of what the State is trying to achieve, with the government saying ‘you’ve got to make people permanent, but you can’t exceed the numbers that we give you’”.

Dr Theresa O’Keefe, sociology lecturer in UCC who researches precarity said that her research with Dr Aline Courtois found that, while austerity exacerbated precarious work, it was always a function of the system. “People who we talked to for our research had been precarious for 14 or 15 years in 2013.”

Big spenders

Trinity College was a close second in terms of spend in the 2019/20 academic year – at over €18.6 million paid to 2,268 non-permanent and casual lecturers. Of these, 2,025 were classed as casual by the university and paid an average of €2,159 per person. The remaining 243 were paid an average of €58,642.

In a statement to Noteworthy, a spokesperson for Trinity said that “in an organisation of this size and complexity, it is necessary to engage people on fixed-term contracts to carry out work that is fixed-term in nature”, adding that they operate within the legislation. “If work is required on a regular ongoing basis, then a permanent contract or contract of indefinite duration is provided.”

TU Dublin was the next highest at over €6.8 million to 761 staff for last year’s figures. A spokesperson for the university told us about their change in policy:

For many years, our predecessor institutions relied quite heavily on the availability of hourly-paid lecturers to enable us to deliver our full range of programmes.

“This dependency has greatly decreased over the last decade as we have sought to recruit staff to permanent roles as a priority.”

The spokesperson added that TU Dublin “is continuing to pursue a policy of minimising the use of non-permanent staff”, but added that “there will always be a need for temporary appointment of academic and professional services staff”.

UCC did not include a figure for last year but paid over €8 million to 2,960 of this category of staff in the previous 2018/19 academic year which was similar to the two previous years it also provided.

Demand for temporary and hourly staff was accounted for by “the surge in student numbers over the last decade” which have grown by more than one-third, according to a UCC spokesperson, as well as the ECF limiting the ability to hire permanent staff.

DCU and Waterford IT did not give us this information through FOI. Waterford IT provided the range of payments they pay through their hourly payment system, with 51% receiving less than €1,000, 20% receiving €1,000 to €2,000, and the remainder in the ranges €2,000 to €20,000.

DCU’s response stated that “a figure for total remuneration is not available”. It continued: “The rates of pay vary from €19 per hour to €90 per hour depending on the role. Some staff would have had more than one contract in each year.”

However, the university provided staff numbers and there were 666 in non-permanent or casual staff employed last year. This was the second lowest number in an Irish university.

Of the remaining ITs, Letterkenny IT and IT Carlow spent the most, with an average of around €1 million each on this category of staff over a three year period.

‘A matter for each institution’

When asked about the volume of non-permanent and casual staff we found, a spokesperson from the Department of Higher Education said that “the decision to hire staff is a matter for each institution, subject to compliance with Government policy in respect of employment numbers and pay policy and are not under the direct control of the Department”. They added:

“The Department is advised [that] the requirement by Higher Education Institutions to engage the services of temporary or casual teaching staff is driven by a number of factors including rapid growth in student numbers, new activities, diverse sources of funding, and philanthropic activity – which may be time bound and/or conditional.”

The issue of occasional workers and hourly paid staff in Maynooth University was discussed at the Public Accounts Committee in October and November last year and responses to questions by the committee around the number of occasional staff, pay for public holidays, pension entitlements as well as grievance policies were answered by the university in both July and December.

The chair Sean Fleming, now Minister of State at the Department of Finance, highlighted one worker at the university who was paid over €20,000 in this way over a six-month period.

They are not temporary or part-time; they just come and go, and it is a case of, ‘We will call you when it suits. Here is the hourly rate.’ However, for some people, that arrangement seems to be continuing for a period of time.

In September, the new Public Accounts Committee discussed employment practices in Maynooth University that were detailed in a letter to the Committee by the college at the end of last year.

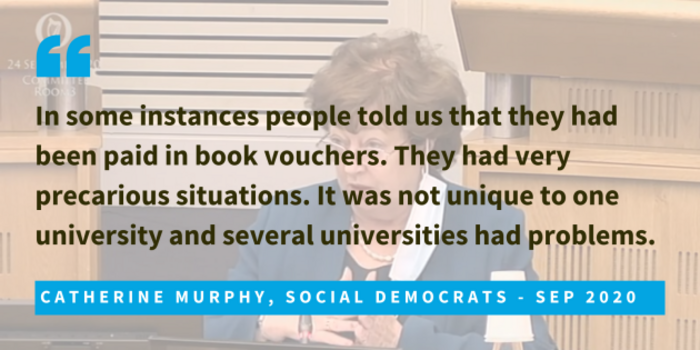

To fill in the new members, Catherine Murphy, joint leader of the Social Democrats, explained some of the issues they encountered previously, including the “high degree of casualisation of work” in the university sector.

“In some instances people told us that they had been paid in book vouchers. They had very precarious situations. It was not unique to one university and several universities had problems. In looking at this, we need to look at not just holidays in line with legal requirements.”

When we put the possibility of staff being offered book tokens as payment to a spokesperson from Maynooth University, they said that “it is certainly not university policy to use book tokens in lieu of pay”.

This was an issue that Noteworthy was also made aware of by lecturers who contacted us, so we sent an FOI request to every university and IT for all records that reference payment for services done by academic staff or students with book tokens or gift vouchers.

Many institutions gave us a breakdown of gift vouchers they gave for purposes such as volunteers or research participants, but none stated that staff were being offered book vouchers in lieu of monetary payments.

A spokesperson for University of Limerick said “it is university practice that vouchers are not used for the payment of services”. No response was received on this query from either NUI Galway or UCD.

Unaccounted working hours

Over the past few months, Noteworthy was contacted by people who are working in or have worked in every university in Ireland as well as a number of ITs. Many were working in jobs they classed as precarious, often paid by the hour and working from semester to semester, with no job security.

Almost all spoke about their inability to get a mortgage, reliance on their partner, impact on family and life planning and their lack of hope about their future career. Almost all had given up hope of gaining secure employment in the near future in a HEI. Almost all felt under-appreciated and overworked.

Similar impacts on mental health and financial stability have been found in numerous academic studies on precarious employment both from Ireland and internationally.

Dr Deirdre Flynn says short-term contracts make planning impossible

Dr Deirdre Flynn says short-term contracts make planning impossible

“It’s something that you go into, because you love the research, or you love teaching,” explained Dr Deirdre Flynn who wrote an essay ‘On Being Precarious’ for the Irish University Review last year.

“You are told that the first few years are going to be tough but think ‘it will be fine’” but, she added, “when you go through it, you realise it doesn’t pay, it’s very hard to make ends meet” after completing your PhD.

“When you’re earning less than the living wage – a good year might be €16,000 to €20,000”. Flynn felt that it is hard without support, especially for those with caring responsibilities. “I’m lucky, I have a partner that can share or take over the bills,” she added – a phrase that nearly everyone we spoke to said at some point in the interview.

Most people we also spoke to that were on a teaching contract at a HEI were paid per hour of lecture or tutorial delivered to students. Rates range from around €12.50 to €85 per hour for teaching, depending on a number of factors including the HEI, the type of teaching with lecturing being higher paid, experience level and if rates are inclusive of preparation time – which is normally the case. ITs and TU Dublin are more standardised as pay agreements are in place with their main union, TUI.

Entrants into the workforce in third-level are also affected by what the TUI call ‘pay discrimination’. For example, new assistant lecturers earn 3% less than those who joined before 2011. TUI members went on a day’s strike in February over this issue.

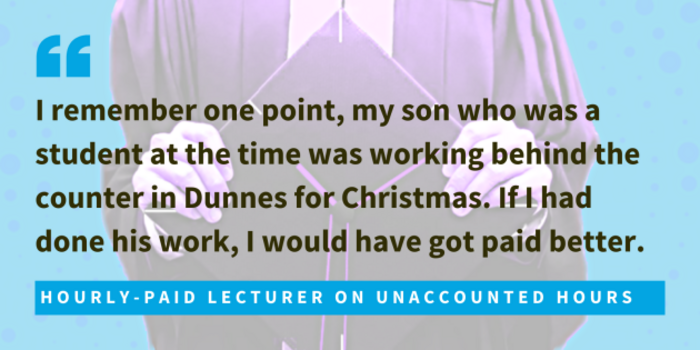

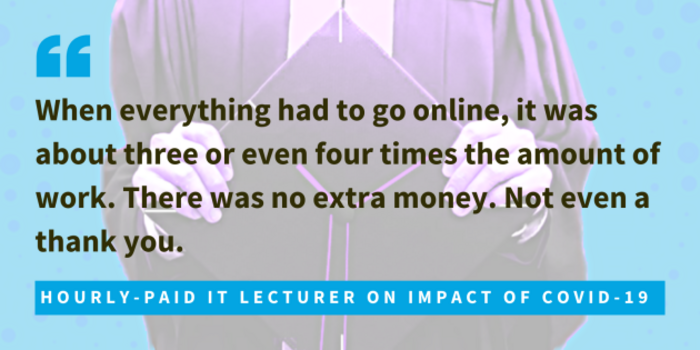

However, though these rates may be high in comparison to other sectors, those who were precariously employed told Noteworthy that this rate drastically reduces when calculated on a per-hour-worked basis. This is due to the work included in that hourly rate which includes preparation of lectures, interaction with students in person or over email, as well as other extras such as planning meetings with colleagues.

“There’s an unwritten rule that one hour of lecturing pay includes three or four hours of research and preparation time,” explained Flynn. However, she added that, since it’s not actually written anywhere, there’s no data captured on those extra hours worked.

In her essay, Flynn wrote that she earned €20,000 in 2018 in spite of having contracts in three different institutions and being out of work for just six week of the year. She also calculated that over the course of five years these HEI contracts added up to approximately 115 months, or nine and a half years of employment, when extra hours are accounted for.

On top of that she conducted research, wrote articles and attended conferences which “is unpaid work” as “in order to be the academic that people want, you have to have the teaching, research and admin – the complete package”.

This was a common scenario for lecturers on hourly-paid or teaching-only contracts that Noteworthy interviewed, with most spending all of their spare time conducting research, which they were not paid for.

“It’s really hard to decide where your life outside of work goes because you can’t plan anything. You can’t say this is the time we can put money away or get married or have kids, because you just don’t know,” said Flynn.

Where the controversy arises

Prof Michael Doherty said that what a CID entitles you to is not well understood in the sector.

Prof Michael Doherty said that what a CID entitles you to is not well understood in the sector.

There are protections for fixed-term workers in place through the Protection of Employees (Fixed-Term Work) Act 2003 in Ireland, which, according to the Cush Report, “provides a framework to prevent abuse arising from the use of successive fixed-term contracts”.

In the Act, “four years is the magic number”, according to Doherty. He explained “if you had more than one contract totalling four years, then you’re in potential CID territory”. For lecturers, Cush recommended that be reduced to two years.

Doherty said that he deliberately used the phrase ‘CID territory’ as the employer can say, for example, that they hired a lecturer on four one-year contracts, but they were for very specific purposes, and those purposes no longer exist.

“That’s where the controversy arises,” he added. “Virtually all of the case law since 2003” has been from education and health public sector “because those sectors have traditionally relied on a lot of contract labour as opposed to permanent posts”.

A CID “converts your existing position to one that is limited by time, to one that is not limited by time”. So if you have been teaching eight hours per week, you will remain on these hours – it “just deletes the end date”.

This is “not well understood” in the sector, Doherty said, with many believing it entitles them to the same pay and conditions as their permanent full-time colleagues.

“The recommendations of the Cush Report have been implemented in full by all universities,” according to a spokesperson for the Irish Universities Association. An agreement was reached between IFUT and the IUA last year on its implementation.

This process was different in ITs due to their different governance structure. A circular sent by the Department of Education and Skills in July 2016 detailed the arrangement and procedures for their implementation.

However, CIDs were, by far, the top issue that we were contacted about by fixed-term and hourly-paid lectures. Many were working for years, in some cases over a decade, with no guarantee of hours or future work.

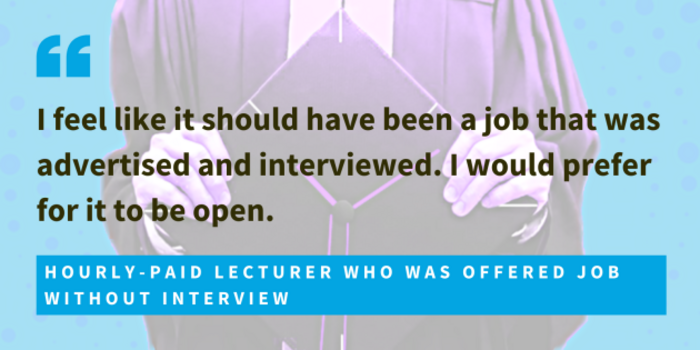

“A lot of these problems in the university sector stem from the very unclear relationship sometimes between a student and an employee,” according to IFUT’s Jones. He explained that many start off as postgraduate students and are then offered some teaching.

“Then next thing they’re fully recognised in the eyes of anyone as employees, but they’ve never had a contract of employment, they have probably never worked outside of the university sector. And they’re probably not union members.”

These types of cases account for about 50% of IFUT’s work. He added that “in fairness to HR departments, these individuals are usually not hired through some sort of form of process, and they’re probably local arrangements”.

Lecturers not on a CID

Through FOI, Noteworthy asked all universities and ITs for the number of academic staff in continuous employment in excess of two years but not on a CID for each of the past three academic years.

Across Ireland, 440 academic staff fell into this category, as per the most recent academic year each HEI provided to Noteworthy.

Data from most HEIs was from 2017/18 up to 2019/20, but others provided a different range, while a small number gave only one or two years. Because of this, the most recent figure we could obtain from each HEI was used to calculate the total.

CID Numbers: We have created a searchable table which lists the full set of CID figures for all years provided to Noteworthy by the HEIs. Click here to explore (best on PC/laptop). A mobile-friendly summary is available here.

Of the universities and ITs that provided this data to Noteworthy, UCD, Ireland’s largest university, had the highest number. This category of staff grew in UCD by almost 50% in recent years with 95 in 2017/18 which increased to 140 last year.

A spokesperson for UCD said “there is no automatic entitlement to a CID after two years’ service”. They added:

“The circumstances where a staff member may have in excess of two years’ service but not have a CID, would include where there is an objective ground for the position being filled on a fixed-term basis… such as arriving at a specific date, completing a specific task or the occurrence of a specific event, that objectively justify the position being filled on a fixed-term basis.”

In terms of last year’s figures, as provided by HEIs, Trinity College had 70 academic staff in this category as of May this year.

A number of hourly-paid lecturers based in Trinity, who had worked on courses over periods from three years to multiples of that, told us of their inability to secure CIDs. They were given hours on a “term-by-term basis” with no future security.

A spokesperson from the university acknowledged the recommendations of the Cush Report and added that “it does not alter any of the other provisions of the Protection of Employees (Fixed-Term Workers) Act in relation to entitlement or award of a CID” and cited a provision that “requires two or more continuous contracts of employment”.

They added that there is an agreed process for staff “to be assessed if they believe they have accrued a CID”.

Unlike UCD, the number of academic staff in this category has reduced in DCU over the past three years from 96 to 42. A spokesperson said: “DCU has granted 65 contracts of indefinite duration to staff since 2017”. They added that “in some of these cases staff have requested such contracts and in others DCU has issued them without a request from the staff member concerned”.

UCC had 63, as of last month. A spokesperson for UCC also gave details about when academic staff are entitled to a CID and mentioned the restrictions placed on them by the Employment Control Framework.

TU Dublin only provided data for Tallaght because, according to a spokesperson, “to compile such a file is a complex task as it needs to take into consideration all of the types of temporary posts in the university.”

All remaining universities and ITs had less than 15 academic staff in this category. Athlone IT, Sligo IT and Limerick IT said “that no staff met this criteria”, “all part-time academic staff who qualified for a CID… were issued with a CID” and it was their practice to grant a CID “after two years of service”, respectively, so answered zero for each of the relevant years.

Cush ‘doesn’t fix precarity’

A number of staff in HEIs who we spoke to told us a variety of reasons that they felt stuck on never-ending short-term contracts, with no hope of a CID. One reason given for this was working in different institutions and not having continuous service in one as entitlement to CIDs does not travel across HEIs.

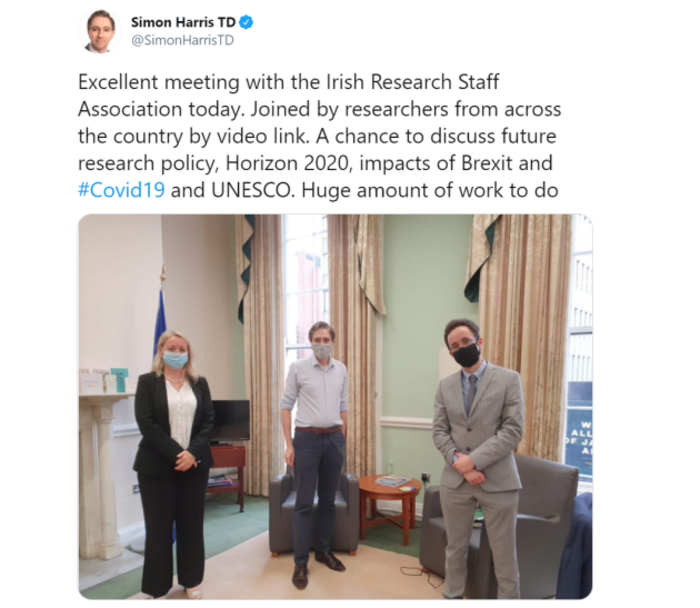

SIPTU’s education sector organiser Karl Byrne said that “Cush was a start but it doesn’t fix precarity”. There is a lot of work that needs to be done, he added. “We have raised it with the new Minister, Simon Harris, who has noted that precarity is something that needs to be looked at.”

Another major issue is that research staff did not come under the Cush Report so they must wait over four years of continuous service to be entitled to a CID – and even if they manage that – many need to work on different projects, funded by different bodies which creates an additional obstacle to long-term employment for researchers.

“It’s more difficult to point to an ongoing purpose if a research project ends and another begins,” according to law professor Doherty. This is different from lecturers where “this academic year ends but the next one is coming in a few weeks”.

Dr Susan Kathleen Fetics, co-director of Women in Research Ireland has worked in research in Ireland as well as France and the United States. She said it’s tough to get a permanent contract at HEIs, but this is not an issue unique to Ireland. “It’s global. It’s happening everywhere. This is a culture of research and science.”

Though data on researchers is not readily available in Ireland, last year the University and College Union in the UK found that around 70% of the 49,000 researchers in the higher education sector there were on fixed-term contracts.

Fetics said this is because of the way research funding is structured where large grants are given to established permanent academics who then hire researchers on fixed-term contracts to complete the work.

I ended up working for four years at Trinity but it was for four different contracts. That’s what happens with people. You come on a short-term contract and perhaps you’ll be here 10 years, but it’s from contract to contract because of the funding.

People on these shorter-term contracts find it difficult to have a voice in universities, according to Fetics, with some not receiving staff emails as they are not permanent staff.

Being excluded or treated differently to permanent staff members was highlighted to us by a number of researchers across Ireland. Other issues included lack of representation on school boards, lack of office space and not being invited to staff meetings, presentations or parties.

It’s very difficult to get out of these short-term contracts into permanent jobs, Fetics explained. “You need to be working seven days a week as weekends are spent catching up on articles and writing grant proposals.” She subsequently left academia to save her “lifestyle and mental health”.

Dr Susan Kathleen Fetics says casualisation of research is a global problem.

Dr Susan Kathleen Fetics says casualisation of research is a global problem.

Groups such as Women in Research can raise awareness of the issue but the systemic problem has to be tackled at a national, Government and broader European level, Fetics explained.

Last year, a joint declaration on sustainable researcher careers was made at an EU level by the Marie Curie Alumni Association and the European Council of Doctoral Candidates and Junior Researchers. The press release at the time gave some background on the issue:

“The number of researchers being trained is growing rapidly in Europe and globally, far outpacing the resources being added in most regions. As a result, researchers are confronted with increasingly precarious conditions, which is disproportionately affecting early-career researchers.”

It cited Eurostat statistics showing that there was a 32.2% increase in the number of researchers employed in EU member states in 2016 compared to 2006. They also cited the mental health impact of doctoral researchers who face six times higher rates of depression and anxiety than the general public.

The groups called on “the creation of more permanent academic research positions, supported by long-term, predictable, and sustainable funding programmes” and concluded:

It is increasingly clear that fundamental, cutting-edge research should not be based on current, short-term funding programmes and contracts.

Another issue being raised in the higher level sector this year is the fact that PhDs are being asked to teach for up to six hours per week in HEIs across Ireland for no extra pay on top of their research grants.

In part three of this investigation, we spoke to a number of postgraduate groups about their campaign to be recognised as workers.

In Ireland, the universities, through the IUA, are developing a Researcher Careers and Employment Framework. This is being finalised currently and “will assist in addressing employment issues and terms”, according to a HEA letter last year.

The IUA told Noteworthy that discussions on the implementation of this “are currently underway with union representatives” and the final version “will be published before the end of the year”.

Departmental report

Noteworthy felt it was important to ask for an interview about insecure employment in HEIs with the minister in charge of this newly created Government Department, Simon Harris.

We requested this with a number of weeks’ notice, and sent regular reminders, but were told by a spokesperson, six weeks after our initial request that Minister Harris is awaiting the contents of a report he sought so an interview could not be facilitated until he could read it and consider the matter in full.

When more information was requested about this report, the Department spokesperson stated: “Minister Harris has met with a number of representative groups who have raised issues regarding employment in research with him. He has asked his Department to prepare a report for him on the issues that have been raised directly for further consideration.” However, no timeline or expected completion date was provided to us by the Department.

One of those groups was the Irish Research Staff Association who met Minister Harris in August. Dr Andrew P Allen, chair of the association said that precarity was mentioned as an overarching theme and they also discussed other issues such as the need to improve data on research staff in Ireland.

He added that one of the key points they brought up was their aim “to get involved in different bodies like the IUA and HEA so they can feed more into the policies that affect the degree to which researchers are affected by precarity”.

Allen said they are following up with the Minister for another meeting and hoping that will happen soon. They are also keen to be involved in the finalisation of the Researcher Careers and Employment Framework but “haven’t seen it as yet”.

‘No central record’ of complaints

In addition to groups such as the Irish Research Staff Association raising the issue of precarity, staff can go directly to HR or their union about these issues.

We asked all universities and ITs for a record of all complaints made by academic staff members about their employment status from 2017 to March 2020. From the varied responses we received, there does not appear to be a standardised system of keeping records of these types of complaints across all HEIs.

Click here to view this searchable table in a different window.

When asked about this, a spokesperson for the IUA said that “any complaints or grievances raised are addressed through agreed procedures, and are responded to having regard to institutional policy, collective agreement, and employment law obligations”.

We received an identical response from a spokesperson from the Department of Higher Education.

Union challenges

Many casual workers in HEIs that contacted Noteworthy had issues with unions, with some saying the monthly membership for IFUT was too high for those on low incomes.

To encourage staff earning less money to join, IFUT are planning to change their membership fees in 2022 from the current model which charges €16 to €35 per month, dependent on income, to one where it is 0.75% of earnings, with a cap of €35. “It does cause a barrier to entry”, said Jones, who added this will be a fairer system.

The lack of temporary staff in unions is an issue in many sectors. Noteworthy previously encountered this in our investigation into the home care sector, where healthcare assistants and home carers were “afraid to be seen in a union” due to fear of getting hours cut as a consequence, according to a SIPTU sector organiser.

Jones said that when people on arrangements such as occasional paid workers come to them with problems, they meet and try to resolve issues but “it’s a challenge” due to some not being defined as lectures or being outside the scope of the Cush Report.

‘Letting the side down’

With many not having a seat at union or management tables, Flynn said that “their voices aren’t being heard”. More senior academics on secure contracts should advocate for their more precarious colleagues, according to the lecturer, who said that a practical way of doing this is questioning the pay and conditions of people being hired by their department.

Professor Peter Coxon, who recently retired from the Geography Department in Trinity College, had a seat on one particular table – the Board of the university.

Coxon said that he never heard the impact of part-time or casual jobs debated at Board level. “There would be people on various bodies, like Board and Council, that would represent various aspects of the college, but I’ve never heard a reasoned debate about this.”

When Noteworthy put this to Trinity, a spokesperson said that “Board discussions are confidential and it is our policy never to comment on them”.

He resigned from the Board in 2015 after speaking out about a separate staffing issue – cutbacks in his department. “If you’re trying to climb a ladder, you’re not going to say something, you just keep your head down”, he explained.

United in precarity

Coxon isn’t the only person we spoke to who had a bad experience of raising these issues. Gyunghee Park, who is currently finishing her PhD in UCC, set up a group called United in Precarity after she began to get “a lot of pushback” when she brought up issues around pay allocation, hiring and teaching at departmental meetings which she attended as class representative.

Park says her experience of working at a number of HEIs has not been easy since she came here from the United States a decade ago.

“In the last 10 years, I’ve had part-time research jobs, tutoring gigs, ad hoc teaching and now a fixed-term position. Across the board, there have been issues with payment, sometimes not seeing a contract, sometimes finding out someone is getting paid three times as much. Last year was the first time I’ve actually made a living standard wage.”

Previously she was teaching around five courses per semester in three different institutions but made less than €8,000 per year. She is currently working in a paid research role but this comes to an end in January when she “doesn’t know what will happen”.

She says that this puts stress on her and her husband in terms of their housing and financial situation. “I remember one time, we were so broke, that we actually had to crack open a giant coin jar that we had to get money for groceries. It’s been really frustrating.”

However, United in Precarity dissolved after a short while as “it’s been very difficult to kind of galvanise because there is this overarching culture”. Park said that people who feel exploited are often afraid to do anything.

Dr Mark Cullinane who is a postdoctoral researcher in UCC was also involved, along with Park, in setting up United in Precarity in UCC. “We produced pamphlets and contributed to union meetings to try to interject some ideas and urgency into matters.”

He said they ran into two main issues which resulted in United in Precarity not working out: Fear, as well as the way that higher level is organised into small units, with some workers interacting with a very small number of people. This makes it more difficult to address issues of casualisation at HEIs, according to Cullinane.

He found casual workers were “afraid to come together lest there be retribution” which, he said, can play out in very subtle ways such as “not getting that call to do teaching”.

Most of the lecturers and researchers that interacted with Noteworthy – even those on more secure contracts – did so on the condition of anonymity because of this fear.

‘Training and development role’

Postdoctoral roles in Irish HEIs are almost exclusively fixed-term training and development roles. For instance, in UCC, where Cullinane is employed, their publicly available policy on Employment and Career Management Structure for Researchers states:

“All Contracts of Employment will be issued to research staff by the Department of Human Resources and contracts shall be issued as follows: On a fixed-term contract basis, this will be defined as a professional training and development role and the professional training and development will be completed within the period of the contract which is issued.”

It also states that providing postdoctoral research training opportunities which are of limited duration is “a legitimate objective of the University” to allow for “the progression, over many years, of large numbers of postdoctoral researchers through the postdoctoral professional training and development programme”

In Cullinane’s experience he does not feel that these are training roles and he hasn’t “really had teaching opportunities within the rubric of the postdocs”. In one of his past positions, his manager discouraged him from attending training due to his part-time contract.

When Noteworthy asked UCC about this, a spokesperson cited a recent research staff survey that found “most researchers agree that they are encouraged to attend training provided by UCC”. They added that “there is an extensive range of supports, academic and non-academic, in place in UCC for research students, whether doctoral or master’s level”.

Funding issue ‘cannot be ignored’

Precarity across the sector ties into the complete underfunding of third level, explained Byrne of SIPTU. He quoted Minister Harris who called this “political cowardice” in an interview on Newstalk last month.

The Cassels Report made a recommendation to significantly increase State funding of the sector in 2016. However, in a letter from the HEA to the Public Accounts Committee in December 2019, it stated that “there have been reductions in overall State funding for the higher education sector since 2008”. It continued:

“From 2008 to 2014 there was a decrease of approximately 20% and from 2015 to 2018 there was an increase of 9%. In parallel full-time student numbers increased by approximately 30% between 2008 and 2018.”

In September, the Committee discussed this letter and in response chair Brian Stanley from Sinn Féin said that “the funding issue needs to be addressed and cannot be ignored”, and added it to their future work programme.

In the same Newstalk interview last month, Harris said the European Union was currently considering an Expert Group report on Future Funding for Higher Education and was due to report back in January. “We need to get the report back from Europe in early 2021 and make a Government decision on it,” he added.

Flynn, like most academics Noteworthy spoke to, is worried that the current funding crisis will be exasperated by the pandemic. She said the way that people are currently hired by universities and ITs on a temporary basis is a “cheap way” to tackle this crisis, “like a little bandage of paper over the cracks”.

“We sell Ireland as the land of saints and scholars. Unless the Government invests in this, they’re going to constantly rely on precarious workers and hourly-paid workers for labour.”

***

As part of our ACADEMIC UNCERTAINTY investigation, part two explores how precarious work is having an impact on diversity in HEIs. Part three delves into ongoing campaigns by postgraduate researchers for workers rights.

This investigation was carried out by Maria Delaney of Noteworthy. It was proposed and funded by you, our readers.

You can support the huge volume of additional work required over the past number of months because of the time consuming FOI requests by supporting the Noteworthy general fund or giving the gift of investigative journalism to a loved one this Christmas.

Noteworthy is the investigative journalism platform from TheJournal.ie. You can support our work by helping to fund one of our other investigation proposals or submitting an idea for a story. Click here to find out more >>