Grade inflation is soaring: Are degrees losing all meaning?

Analysis of awards from Irish third-level institutions by Noteworthy.ie uncovers an upward trend in grades handed to students.

FIRST-CLASS HONOURS and 2.1 grades have increased significantly in most Irish universities, institutes of technology and colleges over the last ten years, an analysis by Noteworthy.ie has found.

The upward trend has led academics and recruiters to warn that third-level degrees are becoming ubiquitous, with employers struggling to differentiate one first-class honours or 2.1 degree from another in their search for top talent, and extracurricular activities and work experience becoming increasingly important for students.

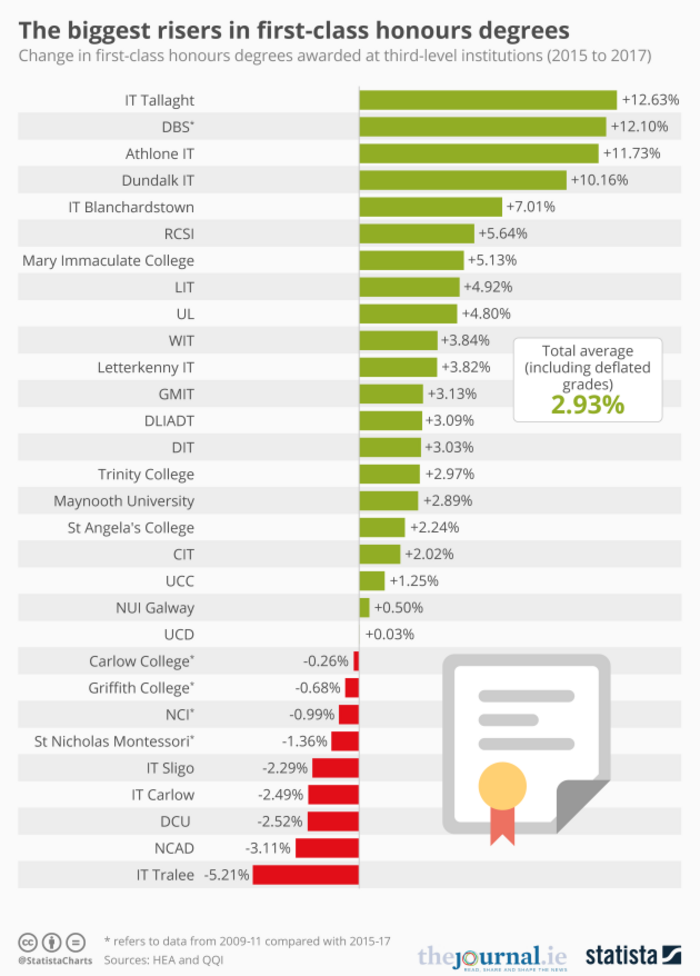

Figures from the Higher Education Authority (HEA) and Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) show that the number of firsts rose by as much as 12.63% in 22 of 30 higher education institutions surveyed. But only 9 HEIs recorded a fall in firsts, with the largest drop at just 5.21%.

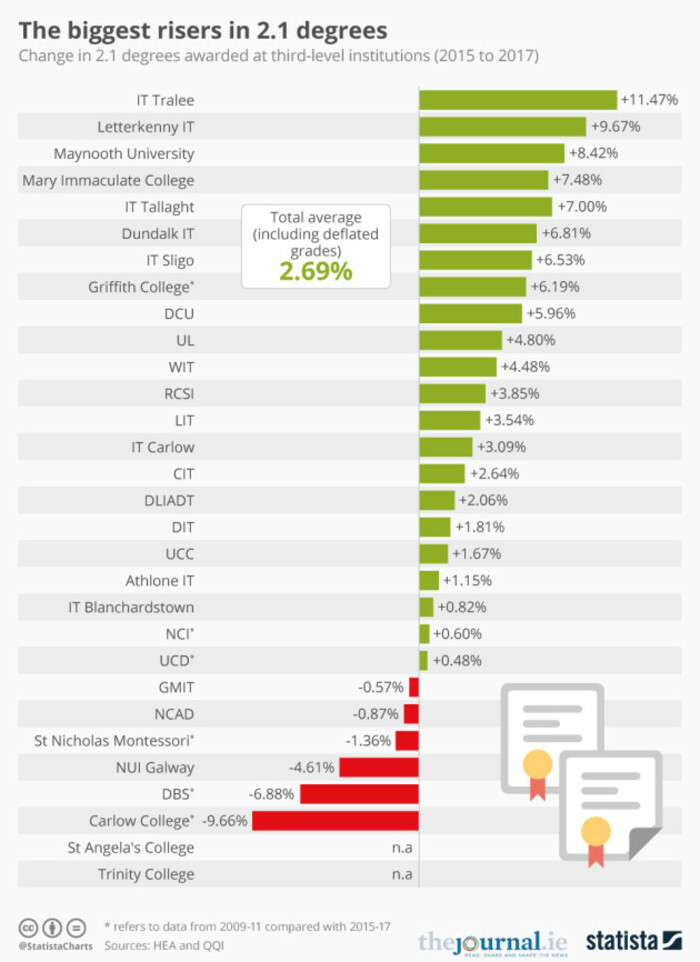

Over the same period, the number of 2.1s awarded to students rose by up to 11.47% across 24 of the 30 institutions, with 2.1 grades down by as much as 9.66% in only other six HEIs.

IT Tallaght, now part of the Technological University of Dublin (which also includes the former Dublin Institute of Technology and IT Blanchardstown), recorded the highest jump in firsts, which rose from an average of 13.69% between 2008-10 to 26.32% between 2015-17, a leap of 12.63%.

This was closely followed by Dublin Business School – the largest fee-paying independent college in the State – which awarded first-class honours to 14.84% of students between 2009-11 compared to 26.94% between 2015-17, a rise of 12.10%.

DBS also awarded a first to 26.94% of its students between 2015-17, with only the Institute of Art, Design & Technology in Dun Laoghaire giving more top grades (26.97%) in the same period.

Meanwhile, the largest jump in 2.1 grades was at IT Tralee, where they rose by 11.47% between 2008-10 and 2015-17, followed by DBS, Athlone IT (up 11.73%), Dundalk IT (up 10.16%), and IT Blanchardstown which has since been incorporated into TU Dublin (up 7.01%).

Most likely to get a first

Having trouble viewing this chart? See here>

The trend towards rising grades is most visible in institutes of technology, although the number of firsts have risen in all seven universities, while 2.1s are up in all of the universities except NUI Galway where they have dipped by 4.61%.

Students at Trinity College are more likely to pick up a first than at any other university in the State, with 19.52% getting top marks compared to 19.24% at the University of Limerick, 19.16% at University College Cork, 15.7% at NUI Galway, 15.68% at UCD, 15.35% at Maynooth University and 14.46% at Dublin City University.

Students were least likely to secure a first in Carlow College between 2015-17, with only 7.89% taking top marks, followed by the National College of Ireland (11.66%), IT Tralee and IT Sligo (both 12.5%) and Mary Immaculate College of Education (12.69%).

Most likely to get a 2.1

Having trouble viewing the chart? See here>

Four of the six HEIs most likely to award 2.1s are universities. Graduates of St Nicholas Montessori teacher training college have the best chance of securing a 2.1 (65.82%), followed by DCU (59.72%), UCD (55.28%), Maynooth University (51.68%), IT Sligo (49.93%) and UCC (49.92%).

The lowest number of 2.1s were at IT Blanchardstown (18.46%), IT Tallaght (24.58%), the Royal College of Surgeons Ireland (28.82%), IADT (30.5%) and Griffith College (32.66%), followed by two of the universities: UL (37.15%) and NUIG (37.91%).

Middle class hunger for honours?

The proliferation of firsts and 2.1s is leading employers to differentiate between graduates based on where they went to college, Brendan Guilfoyle, a professor of maths at IT Tralee and a founding member of the Irish Network for Educational Standards, has warned.

“If everyone is passing or getting high marks, a good award will become increasingly linked to the institution it comes from,” said Guilfoyle, a long-time campaigner against grade inflation in Irish HEIs.

“If standards are so low that everyone gets a pat on the back, those HEIs will go to the wall, and our best third-level students will go abroad to be educated. And, ultimately, it throws into question whether graduates are really gaining the critical skills needed for certain roles.

“Grade inflation is being driven by an insatiable demand for degrees, particularly among the Irish middle classes. This is pushing up participation rates and expectations, and has lowered the pool of talent because people who may have pursued an apprenticeship, traineeship or further education are, instead, enrolling in third-level.

“Institutes of technology, in attempting to become ‘technological universities’, have drifted from their vocational mission. There is pressure on institutions to put more bums on seats, and because HEA funding is partially based on student numbers, it gives colleges a bigger incentive to pass more students.”

“An intolerable strain”

Ireland has a higher proportion of third-level graduates than any other EU country. A demographic bubble means that student numbers are set to rise by 25% over the coming decade – a situation that the Irish Universities Association said last year will “place an intolerable strain on the already under-resourced university system.”

Guilfoyle said that, as he sees it, QQI – the independent State agency with responsibility for accrediting courses and ensuring quality in the further and higher education sectors – is already under-resourced and that accreditation from professional bodies, such as Chartered Accountants Ireland or the Institute of Industrial Engineers, is helping to maintain standards.

Degrees are now held by 56% of 25-34 year-olds compared to 29% of 60-64 year-olds. This is leading graduates to place more value on the classification of their award, Padraig Walsh, CEO of QQI, told Noteworthy.

“Classifications have become more widely used for pre-selection for employment or access to advanced studies, which motivates students to get the highest classification possible,” he said. “This is different in disciplines like teaching and medicine where passing is the key to professional registration.”

For employers, what’s in a grade?

As a result of grade inflation, Walsh said, employers are looking at other factors beyond the grade awarded. “When considering newly graduated candidates for permanent positions, employers often seek references directly from academic supervisors to understand how a graduate performed in comparison to their class or learning cohort, rather than focusing narrowly on the subject grades achieved or the overall classification.”

QQI sets broad frameworks for degrees within the National Framework of Qualifications but makes no specifications on grades or classifications.

Walsh said that public scrutiny of grades, such as this article, places pressure on HEIs “not to undermine their marketing or reputational position by being out of step with their peers by, for example, awarding too many or too few firsts. It also makes it difficult for any individual institution to combat grade inflation by acting unilaterally.”

Norms and expectations may change over time and can be influenced by external examiners, many of which are drawn from the UK. “We may be importing some of our inflation from the league table pressures there,” Walsh observed.

Dr Greg Foley, a lecturer in chemical engineering at DCU, has publicly disagreed that grade inflation should be a cause for significant concern.

It’s starting earlier than at third-level

“The percentage of Leaving Cert students getting 500 points or more has been increasing steadily, so whatever is going on is happening before they start in higher or further education,” he told Noteworthy.

“I’ve been a lecturer for over 30 years and, in that time, there has been extensive change in teaching and learning at third-level. Student learning is much more managed today and this, more than anything, is at the root of students’ improving performance.” But, he added, the increased management of student learning could be creating “a culture where students are highly dependent on feedback and transparency.”

Both Walsh and Foley pointed to changing student expectations and improved teaching as factors behind the rise in grades.

“Students now demand that higher education institutions make clear what is expected of them to obtain a specific qualification with a specific classification,” Walsh said.

“The institutions have obliged, providing far clearer statements of expected learning outcomes, details of how their achievement of these is assessed, more feedback to students on how to improve their performance in assessments, spreading assessment across a wider range of assignments and helping students learn across the duration of the academic year rather than place all their bets cramming for unpredictable, end-of-course ‘finals’.

“These are all features which could broadly be considered as improvements in higher education practice, even if they are offset by factors such as declining resources per student.”

Guilfoyle, however, said that he has never seen any evidence linking grade inflation to modularisation, semesterisation or continuous assessment.

Students taking control of their learning

Lorna Fitzpatrick, president of the Union of Students in Ireland, firmly rejected the idea that grade inflation is caused by a decline in standards. “Grades are rising because students are more involved in the overall learning process, including course design and curriculum development, while third-levels have moved away from traditional assessment to be more inclusive of different learning styles,” she said.

USI president Lorna Fitzpatrick

USI president Lorna Fitzpatrick

One practical effect of grade inflation is that recruiters and employers are looking beyond an applicant’s final score, said Mike McDonagh, managing director of Hays Ireland, the Irish branch of one of the world’s largest recruitment firms.

“Less organisations demand a 2.1 than in the past, although it become a factor where the volume of applications is high and they need to screen and reduce them. There are still some sectors where employers can have their pick of graduates, particularly in large accounting firms and law. But if over 50% of graduates have a 2.1, it could lose some meaning for employers,” he acknowledged.

“At the moment, skills shortages are acute in certain sectors, and we are seeing some companies drop a once-rigid demand that their staff have a degree, because a degree can bring uniformity whereas they want variety and flexibility. Further education and training can also provide more flexibility and diversity.

“The experience of college remains valuable, but employers are increasingly differentiating between graduates based on their work and voluntary experience, involvement in college clubs and societies, lateral thinking, social skills and ability to work as part of a team and their final project or thesis topic. There is less emphasis on technical skills that, in the future, could be replaced by artificial intelligence, and more on [soft skills such as] lateral thinking.

“There are still some organisations that want graduates with a first, but today that candidate may be overtaken by someone who has more work experience and better conversational skills,” he said.

USI has repeatedly raised concerns that growing financial pressure on students, coupled with increased academic workloads through continuous assessment, semesterisation and modularisation, as well as the growing demand from employers for graduates who developed holistic skill sets through work experience and involvement in college extracurricular life, is unsustainable.

“Students today have more competing priorities than ever before,” said Fitzpatrick. “They are trying to engage in extracurricular life, balance a course load that is very different from even 10 or 20 years ago, and often work part-time to pay extortionate rents and some of the highest student fees – we call them a ‘student contribution’, but they are fees – in the world.

This is in the context of a means-tested student grant [capped at €5,915 for the highest possible SUSI grant] that comes nowhere near covering the cost of rent, let alone food, books and transport.”

Fitzpatrick questioned how students are supposed to be active in extracurricular activities when many are already missing classes to do part-time work.

“We all know that employers today are looking for more than just academic excellence, but we are reaching a point where only those from a better financial background will be able to attend college and get as involved in college life as needed. The Uaneen module in DCU is a good example of how HEIs can engage with students to support extracurricular life.”

Critics of grade inflation, from across the education sector, argue that too many school-leavers are going into third-level when they may be better suited to further education and training including Post-Leaving Cert, apprenticeship and traineeship courses.

Loss of apprentices

The number of apprentices is up from the recession low of 1,200 to 16,000 and rising but Solas, the further education and training agency, wants to see it climb further. Solas is also keen to highlight that there are over 30,000 places available on post-Leaving Cert courses, which can serve as a qualification in their own right as well as a bridge on to third-level.

Figures show that just under 20 per cent of PLC graduates progress to higher education and also account for 20 per cent of the overall first-year intake at institutes of technology and the Technological University of Dublin (this figure excludes mature entrants who came through PLCs).

Earlier this year, a survey carried out by Solas, QQI and the HEA found that 86% of employers were happy with the quality of higher education graduates and 84% were happy with further education graduates. Employers placed a slightly higher rating on further education graduates when it came to teamwork and enterprise skills. This may be because Solas, which has a specific vocational remit, must work closely with employers to design courses that meet specific skills needs.

Nikki Gallagher, director of communications with Solas, said that young people should consider their interests, aptitudes and where the jobs are when making their post-secondary school options.

“We hear very positive feedback from employers about how work ready FET grads are, we also know that there many people who do FET courses progress to third level and do very well. We would certainly encourage anyone who is unsure if they are ready for third level to consider a PLC course – and there are a huge number to choose from. We have evidence of a very high third level completion rate of those who do a FET course first.”

Caveats and notes

Reliable data on the number of 2.1s awarded at Trinity College and St Angela’s College in Sligo was not available. This is because QQI provided data on grades at five institutions from the year 2009 to date: Carlow College, Dublin Business School, Griffith College, National College of Ireland, St Nicholas Montessori teacher training college. Data for 2008 was not available for these five institutions and we have therefore used figures from 2009-11 and compared them with 2015-17.

Due to a change in how degrees at UCD were classified until 2008, the figures provided for UCD are from the year 2009-11 instead of 2008-10.

The Dublin Institute of Technology, IT Tallaght and IT Blanchardstown merged in January 2019 to become the Technological University of Dublin. As our figures date only as far as the 2017 academic year, our analysis treats the three institutions as separate; they are categorised here as three institutes of technology rather than one university.

GRADE INFLATION: WHAT THE COLLEGES SAY

Carlow College gave out firsts to just 7.89% of its students between 2015-17, representing a fall of 0.26% compared to 2009-11. “We are proud of our rigorous academic standards and have actively sought to avoid grade inflation while producing high-achieving graduates, and this has been noted with approval by external examiners,” a spokesperson for the college said.

A spokesperson for DCU said: “Given the active role of our external examiners, and our close attention to quality standards, DCU is confident that the distribution of grades in any given year reflects the quality of our students benchmarked against the best international standards.”

TU Dublin, which was formed this year from a merger of DIT, IT Tallaght and IT Blanchardstown, said that all students are assessed on their individual merits. “It is not our policy to increase the number of 2:1 and 1st awards in order to meet any national benchmark metrics.”

The National College of Art and Design in Dublin 8, a recognised college of UCD, has held the line against grade inflation. The number of firsts are down by 3.11% between 2008-10 and 2015-17, while 2.1s are down by 0.87%. Is this by accident or design?

Dr Siún Hanrahan, NCAD’s interim head of academic affairs, told Noteworthy that modularisation and changes to assessment are behind the dip. “Modularisation was introduced across all of NCAD’s programmes in 2013. This involved structuring curriculums as a planned series of self-contained units. There is some loss of flexibility in terms of reviewing a student’s learning achievement across the year as a whole, and this can have a slight dampening effect.

“NCAD’s move to grade-based assessment, where students are marked in terms of grade (A+, A, A-, B+ etc) has also had a dampening effect at the highest levels of achievement. The changes are due to changes in regulations, rather than being linked to student performance, or a specific effort to tackle grade inflation.”

DBS, which awarded the second-highest amount of first class honours and also had the second-highest percentage rise in firsts over a ten-year period, said it is happy with the standard achieved by its students and that it has “a robust academic quality assurance system” which includes academic leaders, academic teaching staff, external examiners and QQI.

A DBS spokesperson said that they had increased their student supports in recent years with investment in academic and pastoral care for students, while data analytics are allowing it to identify students at risk and to intervene.

At IT Sligo, communications manager Aidan Haughey said that grades are rising because the institute is offering more courses and has higher student numbers with a greater emphasis on support services.

“Our smaller class sizes allow our lecturers to spend more time with students which in turns allows them to achieve better results. The competitiveness of the jobs market has added pressure on students to achieve an honours degree. We have also seen an increase in students wanting to further their studies through a masters (degree) which requires at least a 2.1 in most cases. We hope to improve these results further… as we head towards becoming a technological university with Letterkenny IT and Galway-Mayo IT.”

Dr Nicholas Breakwell, CEO of St Nicholas Montessori Society, said that graduates of the Montessori teacher training college have the highest number of 2.1 grades for a number or reasons, including that education graduates have the highest completion rate at 91% compared to an average across disciplines of 76% and that education students may be better prepared academically and have more supports.

“We employ the full range of QQI quality assured processs and procedures, including an independent external examiner. Ensuring a fair and transparent process for each individual learner is far more important than seeking to adhere to a distribution of grades in an effort to align with other providers who are very different in terms of programmes offered, mode of study, aptitude of learners on entry, number of overseas, mature, part-time learners.”

For more about how to support Noteworthy’s work, visit our website.