The ugly side to dermal fillers: 'Would you let your mechanic stick a needle in your face?'

Demand for lip and facial fillers is booming across Ireland, fuelling concerns about rogue operators in the unregulated beauty industry.

EARLY IN 2017, the vision of beauty blogger AJ Fitzsimons receiving a lip filler treatment beamed into the living rooms of middle Ireland.

Although fillers had been around for decades, the sight of them being administered to the online influencer in front of a national Late Late Show audience could be considered the moment the procedure went mainstream.

The appearance, which accompanied former Miss Ireland Amanda Brunker’s Botox treatment, led to a reported spike in enquiries to cosmetic clinics across the country – as well as a spike in complaints to the RTÉ switchboard.

Just over two years later, it was the same platform that highlighted the ugly side of the industry as former model Carol Bryan told host Ryan Tubridy how she was left disfigured and blind in one eye after a botched filler treatment, a telling bookend to the earlier segment.

Although no firm figures for the popularity of the treatments exist for Ireland, there is little doubt that filler procedures have exploded in frequency – particularly among young women seeking the kind of Instagram-friendly looks popularised by celebrities and reality TV stars.

But demand for the unregulated procedures – the materials for which can be bought cheaply online by anyone – has also fed a boom in non-medical practitioners like beauticians carrying out the procedures.

That puts the public at risk of severe side effects, experts say, fuelling an increasing number of appearances at Irish hospitals’ emergency departments for people with alarming complications that risk turning into life-changing injuries like those suffered by Bryan.

Hyaluronic acid

While collagen injections were once synonymous with plumped-up, smoothed-out skin and lips, those treatments have largely been superseded in recent years by hyaluronic-acid based dermal fillers sold under brand names such as Juvéderm and Restylane.

Unlike Botox, which uses a neurotoxin to effectively paralyse facial muscles in order to soften wrinkles, hyaluronic acid absorbs water after injection to give the skin a fuller, softer look.

The substance occurs naturally in the human body in joints and tissues, but commercial injectables come from more obscure origins: either grown in a lab from bacteria or, more bizarrely, extracted from the combs of roosters.

The effect of fillers typically lasts between six and 12 months, however some of the newer fillers boast wrinkle-busting and plumping effects that last up to two years.

Overall, the filler procedure is considered to be low-risk compared to many cosmetic treatments with most problems linked to how the injections are carried out.

Those injections are typically delivered in 1ml or 2ml doses, however prices vary widely. In a high-end clinic run by specialist medical staff, customers can pay €500 or more for a single treatment.

Several of the largest clinics and chains say they only use doctors to administer injections, while other also have dentists and nurses on hand to provide the treatments.

However the high demand and lucrative nature of the treatments – which can be delivered in sessions lasting fewer than 30 minutes – has also attracted operators charging a fraction of that sum for procedures carried out in beauty or hair salons, tattoo parlours or even people’s homes.

The Jenner effect

Fillers’ leap from being largely a procedure for older patients looking to restore their youthful looks to the must-have treatment for younger women has been put down by some to the influence of one woman: Kylie Jenner.

After the then 17-year-old admitting to getting lip fillers in a 2015 episode of Keeping Up With The Kardashians, chasing her look has been a theme among visitors to many Irish clinics.

Worldwide, hyaluronic acid-based injectables were the second most common procedure performed in 2017 – behind only Botox – according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. The vast majority of the procedures are carried out on women.

Nevertheless, among local beauty influencers, the treatment still carries something of a taboo, with many models and bloggers remaining coy on their use of procedures.

Several prominent Irish bloggers declined to be interviewed for this article, with one raising concern they would be targeted with negative comments for being seen to encourage young women to seek out the treatment.

There is also a noted divide in the clinics’ approach to customers: while some shy away from serving clients looking to augment their appearances, others actively court young women with social media ads featuring pouting models promising the perfect lips.

While there has been no research to gauge the size of the market in Ireland, the country’s largest chain of cosmetic clinics, Therapie, estimates to have had 30,000 people walk through its doors for dermal filler treatments alone in the past year.

The company’s CEO, Phillip McGlade, said that his clinics turned away around one-fifth of potential clients and that was often because of unrealistic goals based on social media and reality TV.

“A lot of the younger girls are coming in looking for lip fillers and we tell them we believe that you don’t need this,” he said.

I think people’s expectations have increased, but one thing we make sure of is that we’re honest and transparent with these clients: you’re not going to look like Kylie Jenner.”

Kylie Jenner

Kylie Jenner

Unregulated

Unlike Botox, which as a prescribed drug can only be administered by doctors and dentists, dermal fillers are classified as medical devices, which leaves them subject to only the loosest of regulation.

In Europe, medical-grade fillers are required to simply bear the CE quality mark, which signifies only that the product has met certain production standards but does not represent proof of its effectiveness.

Several hundred different hyaluronic acid-based fillers are on sale within the EU, a situation in stark contrast to that in the US, where only a handful of fillers – including Restylane, Juvéderm and others commonly offered in well-known clinics here – have received FDA approval as prescription-only devices.

In Ireland, doctors, dentists or nurses performing cosmetic procedures have to answer to their relevant professional bodies if they are on the receiving end of an official complaint, however there is no such oversight for non-medical practitioners.

There are also no age limits on who can receive non-surgical treatments.

For the better part of a decade, industry figures have been sounding the alarm about the potential dangers of fillers in an ever-increasing number of untrained and unchecked hands.

One plastic surgeon warned in a 2013 interview that dermal fillers would be “the next big scandal of the cosmetic industry”, the successor to the PIP breast implant disaster.

Although that scandal has not come to pass, there has been a steady drip of horror stories of bungled treatments.

While most side effects from fillers are mild – usually pain, bruising or swelling after a treatment, or ‘bumps’ where the filler has built up under the skin – severe complications like blindness, skin necrosis and infection centre on incidences of ‘vascular occlusion’ caused by the procedure.

This occurs when the hyaluronic acid is mistakenly injected into a blood vessel, which becomes blocked. Nearly 100 cases of blindness had been reported worldwide from the treatments before 2015, according to one study.

Records obtained by Noteworthy, the investigative journalism platform from TheJournal.ie, show that four formal notifications relating to dermal and lip fillers have been received in the past three years by the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA).

The authority is charged with monitoring the safety of drugs and medical devices available in Ireland. That figure was second to only breast implants, which drew 16 notifications, among all cosmetic treatments.

In one case, from early 2016, a user reported that they had developed an “infective lesion” on their face two months after a filler injection, requiring antibiotic treatment.

A second, from March 2018, involved vascular occlusion after a patient received fillers to reshape their nose. They were given corrective medication after reporting pain and redness.

The Competition and Consumer Protection Commission has also fielded a handful of complaints relating to fillers in recent years. One woman said a Dublin clinic had pressured her into receiving costly filler treatments that she didn’t want after a “railroading” five-minute consultation.

The after-effects of Carol Bryan's botched filler treatment

The after-effects of Carol Bryan's botched filler treatment

Fix-up jobs

Anecdotal evidence points to a significant increase in complications from dermal fillers in recent years, although there is no official data to establish the extent of any problems or from which practices they have originated.

Several cosmetic clinics said they were dealing with increased numbers of fix-up jobs for botched fillers carried out elsewhere, while there have been reports of patients turning up at hospital emergency departments after suffering complications from the treatments.

Earlier this year, Dr Gerry McCarthy, the clinical lead for Ireland’s emergency medicine programme, wrote to emergency medical specialists to alert them to the possible complications from fillers after becoming aware of “a number of presentations” involving vascular occlusion.

The treatment for vascular occlusion is a follow-up injection of hyaluronic acid’s antidote, hyaluronidase. This enzyme breaks down hyaluronic acid, clearing up blocked arteries caused by filler injections.

However unlike the dermal fillers themselves, hyaluronidase is a prescription-only drug in Ireland, which means only doctors, dentists and prescribing nurses can access the medication.

An earlier email from an emergency programme manager, obtained by Noteworthy, warned of the urgent need to ensure emergency doctors knew how to treat botched dermal fillers.

“My fear here is that if (there is) a further case where someone ends up with theoretically ‘preventable’ permanent damage and we haven’t done anything, this could blow up into an unnecessary storm. I have a funny feeling about this one,” she wrote.

Professor Jack Kelly, a consultant plastic and reconstructive surgeon at University Hospital, Galway, said he had dealt with three cases where patients had needed “significant” surgery under general anaesthetic to deal with complications from fillers.

In one instance, the patient had developed a chronic inflammatory response to cheek fillers causing the skin to scar and retract, leading to a “hollowing” effect.

“Unfortunately the problem is that patients usually revert back to their family doctor when they have a complication, and they’re usually referred on,” he said.

“Some people who are giving fillers don’t know how to deal with the consequences when it goes wrong and where to refer to; it’s a big problem.”

Cheap prices, cheap products

In the UK, figures from Save Face, a government-approved register of practitioners who carry out non-surgical cosmetic treatments, showed that around two-thirds of the complaints it logged in 2017-18 related to dermal fillers.

Lip fillers accounted for the largest share of the complaints with swelling and bruising, followed by lumps and nodules, the most common issues identified.

The Laser and Skin Clinic, which has outlets in Dublin, Mullingar and Athlone, is the only provider in the Republic of Ireland to have signed up for the register, which is open to registered nurses or midwives, doctors, dentists or prescribing pharmacists with specialist training.

The chain’s owner, Anna Gunning, who is a nurse, said while fillers were often perceived as a low-risk procedure, in the wrong hands it became a high-risk treatment.

“Even the best injectors in the world can have complications. There are a lot of cheap fillers and people offering cheap prices,” she said.

“Customers are buying lip filler treatments for €120 and €150 and they don’t know what they’re getting – some people are doing it in their houses, in beauty salons and hairdressers.

That’s where the problem lies: people are doing one-day training, they’re using cheap products – sometimes they even put the cheaper product in another box. A lot of them just have a Facebook page, and they disappear when something goes wrong.”

Many of the budget deals appear only on social media, which offers a cheap way for clinics to reach potential clients – with some using ‘like and share’ competitions to give away filler treatments in order to boost their followings.

In some cases, hair, makeup or nail salons advertise ‘pop-up’ filler clinics, with many using the lure of special discount offers for customers who bring along a friend for treatment.

“Have the most amazing lips possible, life is to (sic) short not to,” one tanning and hair salon announced.

Many of the beauticians and non-medical clinics advertising fillers were reluctant to speak publicly when contacted for this article, while others played down their involvement in the industry saying the injections were only a small supplement to their main businesses.

A cottage industry

Alongside the rise in demand for fillers and the numbers of medical and non-medical clinics carrying out the procedures, a cottage industry in providing training for those looking to perform the injections has also sprung up.

Courses typically last one or two days, with the majority open only to registered medical practitioners.

However some UK-based trainers have also begun offering training to beauticians and other non-medical providers in Ireland through partnerships with local providers.

One Dublin clinic offers a course held over two days for €4,000 provided by Manchester training provider Cosmetic Couture, with the Irish firm adding on its website: “With just 5 treatments per week – see your salon revenue rise by 130,000k per year.”

Cosmetic Couture CEO Maxine Hopley said that her company held training sessions in Ireland around three or four times a year and the students were a mix of medics and non-medics.

“The biggest part of the course is adverse affects. At the beginning of any course we talk about how to recognise things like bruising, vascular occlusion, anaphylaxis – we look at real images of adverse effects and what the protocols would be in those situations,” she said.

Hopley added that she believed there should be mandatory registrations and inspections for clinics carrying out the procedures, and that beauticians injecting dermal fillers should only work with medical oversight.

Beauty therapists are in this industry already, so we need to make sure there are proper regulations for them. Why exclude them, why send them to the black market?” she said.

A voluntary register for cosmetic practitioners was opened in the UK last year to help customers identify properly trained providers, however it was subsequently closed to non-medical members after doctors and nurses threatened to boycott the system.

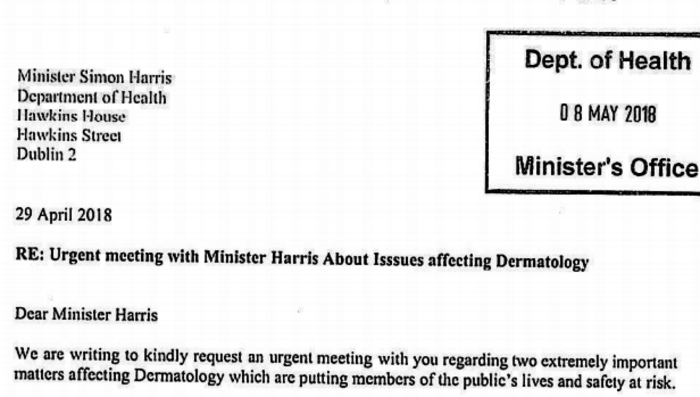

Professor Caitriona Ryan, a consultant dermatologist at Blackrock Clinic, wrote to Health Minister Simon Harris last year after seeing the training course being advertised for beauticians in Dublin.

“We would like to see regulations put in place as soon as possible restricting the use of these fillers to doctors who are formally trained in the complex anatomy of facial vessels and nerves,” she told Harris.

We are asking you to act urgently to prevent non-medically trained individuals from injecting fillers as dangerous complications are inevitable.”

An excerpt from Ryan's letter

An excerpt from Ryan's letter

Self-administered fillers

Ryan told Noteworthy that one of her biggest concerns was seeing some clinics charging less for treatments than the purchase price of medical-grade products.

“That, to me, is frightening, because I can’t imagine what is being put into people’s faces,” she said.

Some of the manufacturers behind the best known-brands, such as Juvéderm maker Allergan and Restylane supplier Galderma, only sell their products to licenced medical practitioners.

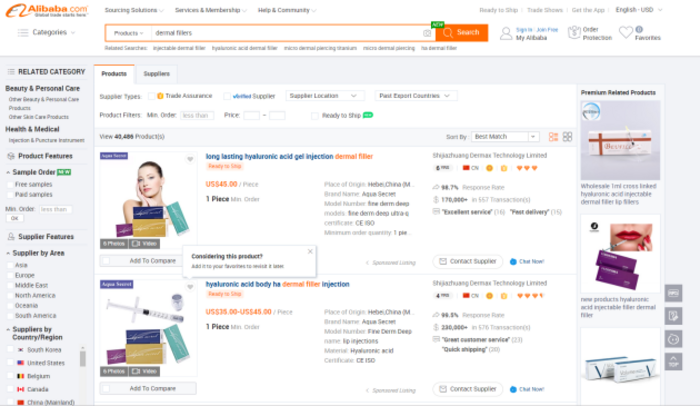

Their fillers can, however, be bought over the internet from third-party sites. Meanwhile, e-commerce giants like Ebay and China-based Alibaba provide a treasure trove of cheap fillers, some costing as little as €10 per 1ml syringe.

Local operators are also responding to the demand with one Ireland-based online seller, Filler Boutique, advertising syringes of injectable fillers starting at less than €50.

Ryan said one client recently reported that his wife had injected filler into her own cheeks and the results were “awful”.

“That is terrifying, that somebody’s at home in their bathroom injecting fillers while looking at themselves in the mirror,” she said.

While Revenue can pass on any fillers to the HPRA that it believes are being illegally imported, such seizures are rare as any CE-marked dermal fillers can legally be obtained and used by any party.

Insurance can also be an issue for beauticians and other non-medical clinics offering dermal fillers, with several major firms that service the sector confirming that they don’t cover injectable treatments.

Fillers can be bought online from the likes of Alibaba

Fillers can be bought online from the likes of Alibaba

The prescription

While most working in the non-surgical cosmetic procedures industry believe tighter regulation is needed when it comes to dermal fillers, opinions differ on how best to crack down on rogue operators.

Cork entrepreneur Pat Phelan, who last year launched the Sisu clinic chain with doctors James and Brian Cotter, said fillers should be classed as a medical drug available only on prescription like Botox or hyaluronidase, the hyaluronic acid antidote.

That would effectively limit those with access to the product to doctors, dentists and prescribing nurses.

“We had a girl who presented to us a few weeks ago with a really badly damaged lip. She had got fillers in her lip in a tattoo parlour,” Phelan said.

I just find it highly dangerous. This is a medical procedure – would you allow your mechanic to stick a needle in your face?”

In its official advice to patients on fillers, the US FDA recommends patients only see licenced health professionals with experience in dermatology or plastic surgery, warning: “Having filler injected should be considered a medical procedure, not a cosmetic treatment.”

Others, however, believe that regulation of the clinics delivering the treatments is the most pressing concern.

Therapie’s McGlade said a government body should have oversight of cosmetic clinics and this organisation ought to be given the power to investigate any complaints against rogue operators.

“I think by bringing in legislation (like that) it will get rid of all the cowboys and the treatments will be administered properly,” he said.

Waiting for disaster

For now, the responsibility lies very much with customers to check the credentials of those administer their fillers: a task made difficult by haphazard training standards and the absence of any licensing system for practitioners.

Many in the sector believe that where UK authorities lead Irish officials are likely to follow. However across the Irish Sea the movement towards tighter regulation has been moving at a glacial pace.

A 2013 review into the aesthetics industry recommended that only those properly trained and qualified to carry out non-surgical cosmetic procedures should administer treatments like dermal fillers unless supervised by a clinically trained overseer.

The review’s head, NHS medical director Bruce Keogh, described the industry as “a crisis waiting to happen” at the time. Since then, there has been little action despite a steady drip-feed of horror stories about treatments like fillers in the British media.

A system of self-regulation and oversight has instead largely filled the regulatory void with organisations such as the Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners active in accrediting clinics.

The council is currently running a campaign to make fillers a prescription-only treatment. Meanwhile in Ireland, it remains unclear how potential legislative changes will affect the industry.

The government is currently drafting the Patient Safety Bill, which would require any providers of ‘high-risk healthcare activities’ – even those taking place outside hospital settings – to require a licence to operate.

While this would extend to some cosmetic procedures, no decision has been made on what types of procedures will be covered under the legislation.

New EU medical device regulations will also kick in next May with the regulations setting out the scope for member states to bring in national legislation to restrict the use of certain devices, like dermal fillers.

“The Department of Health is working with the HPRA to identify the correct use of this provision and how it may be applied to the administration of dermal fillers in Ireland. Work on developing this requirement will continue over the coming months,” a department spokeswoman said via a statement.

However dermatologist Ryan fears that regulatory situation for fillers is unlikely to change unless a major problem – like the PIP scandal for breast implants – forces the government’s hand.

In Ireland, my big fear is that it takes something really really bad happening for them to go and change the legislation and put safeguards in place. It’s going to take somebody going blind.”

Know more about this story or want to share your experiences? Email the author via peter@thejournal.ie or send a message using the secure Threema app, ID: ESUCBYMK

For more about how to support Noteworthy’s work, visit our website.