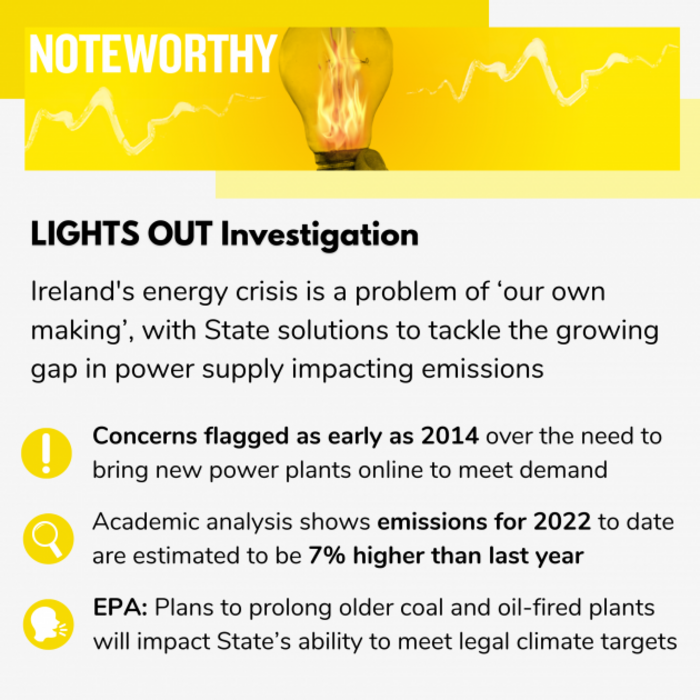

‘Heads must roll’: Industry and experts argue energy crisis of ‘our own making’

Concerns flagged as early as 2014 over the need to bring new power plants online to meet energy demands.

—

“A slight wrap over the knuckles.”

This is how one of the directors of the Commission of Regulation of Utilities (CRU) described Minister Eamon Ryan’s reaction to a request the regulator had just made.

This all happened back in June 2021. The CRU wanted to direct EirGrid to secure a whopping 200MW of emergency generation but before they could do this, they needed the Climate Minister’s permission.

The situation was serious, with the move deemed vital to warn off what EirGrid, Ireland’s electricity operator, described to the CRU as a substantial risk of an electricity security of supply emergency that winter.

The reply that Minister Ryan sent to the CRU reflects this and appears to give more than a minor reprimand. In the letter, he stressed it is “incumbent” on the CRU to consider how this situation arose, including why market structures were “not delivering” the level of new energy generation needed to keep the lights on.

This is exactly what Noteworthy set out to do in our LIGHTS OUT investigation as we examined how we have ended up in a situation where Ireland is in the middle of another bleak winter energy forecast.

To figure out how we got into this mess, we spoke to energy industry insiders, electrical engineers, and energy policy experts, as well as sifting through a decade of reports, data and meeting minutes from State bodies responsible for keeping the country from the jaws of an energy crisis.

We also sent over 30 Freedom of Information (FOI) and Access to Information on the Environment (AIE) requests to State authorities to find out when they were aware of the looming energy crisis, and what they were doing about it behind closed doors. We can reveal:

- Energy industry players warned authorities as early as 2014 that the design of a new energy capacity market – the primary driver of investment in new power stations – would fail to bring the required new plants online

- Concerns were also raised about price caps being too low and lead-in times to build new units being too tight

- The State wants to keep older coal and oil plants in operation despite looming deadlines for them to shut up shop as they fail to meet new EU emissions standards

- Emissions for 2022 to date are estimated to be 7% higher than last year due to increasing use of coal and oil to shore up supply gaps, academic analysis shows

- The EPA has warned that firing up older plants to make up the current power gap will make it very difficult to meet our legal climate targets

—

Ireland has a severe shortage of capacity on the power grid to meet demand

Ireland has a severe shortage of capacity on the power grid to meet demand

Crisis of our own making

In the end, despite Minister Ryan signing off on it, emergency generation was not procured last winter. While we have avoided blackouts so far, the situation remains tense, with a number of amber alerts already issued this year.

The problems we are now facing seem a million miles away from the mid-2010s when there was little concern about future power gaps in reports from State bodies. At that time, there was a large surplus of over 1,000 MW of energy capacity – enough to provide electricity for 1 million Irish homes for a year.

EirGrid estimates in 2015 gave confidence that there was sufficient generation capacity to cover peak energy demand for the next decade. This changed very quickly, however, with the organisation warning since 2016 of “an increasing tightness between demand and supply”.

The rapid expansion of the energy hungry data centre sector has played a big part in the unparalleled growth in electricity demand, predicted to boom by 38% in less than 10 years – between 2017 and 2025. This is equivalent to the demand growth rate in the 50 years between 1930 and 1980, including the entire rural electrification programme.

This demand has now collided head first with a reduction in the availability of older power stations as scheduled upgrades bump up against unforeseen breakdowns. On top of this, vitally important new generation units were not built as planned for various strategic, technical and regulatory reasons.

Now, we are looking at a situation over this winter where we face a potential risk of insufficient generation to meet demand for periods totalling up to 51 hours, well outside the eight hours per year risk level we have adopted in Ireland.

To address this, a range of policy measures have been implemented to encourage the development of new gas generation “as a national priority”.

The effort to close this gap now has come too little, too late, according to industry players and energy experts, who told us that the genesis of the current crisis dates back to the redesign of capacity payments in the early 2010s.

- Yesterday, Noteworthy examined the impact of data centres on the grid and the sector’s emissions that are rising in tandem with growing energy needs.

Capacity payments – change in the air

Alongside payments for power fed into the electricity grid, capacity payments have an equally important role in ensuring that there is enough back-up available that can fire up at peak demand periods and maintain a supply-demand balance at all times.

This is vital as we have limited interconnection to other EU countries, and, as Ireland undergoes its ambitious transformation to a renewable first electricity system, efficient gas-fired power is needed now when wind and solar output levels are low.

While renewables are core to our decarbonised future, the need for conventional back-up power remains, according to Paul Deane, an energy researcher at University College Cork (UCC). “When it isn’t very windy or isn’t very sunny, we do need something to keep our electricity going in Ireland and that’s just a matter of physics.

“This is why we had these capacity auctions to fulfil the need for power plants to jump into the breach,” he said.

Traditionally, fixed payments were distributed by the CRU among all generating units offering capacity, but a new competitive auction-based system was set-up in 2017 “after more than four years of extensive consultation and engagement with industry stakeholders”, according to the CRU.

The CRU is responsible for the design and rules of the Capacity Remuneration Mechanism (CRM) and EirGrid operates the auctions on its behalf.

The CRM is meant to lead to the build-out of plants that could send power to the grid when needed. So far, however, Deane said that this is “where we failed” as we have seen zero new builds in recent years.

So how did we get here? According to several industry players and energy experts, there were several significant kinks in the design of the market around low price caps, supports for new power stations, and short timelines to complete projects that have failed to go unanswered.

And if you speak to Richard Walshe, a 30-year veteran of the power generation market, these issues are not new. Walshe has a large portfolio of projects, mainly onshore wind, but one project that he experienced significant difficulties getting off the ground was the Grange Backup Power plant. But not for want of trying.

Ticking all the boxes

The 115 MW facility would have fast start-up times, high flexibility and higher efficiency, exactly what is required when the electrical grid needs a top up to meet peak electricity demand times and to step in when the wind is down on a calm day.

Grange seemed to be ticking all the boxes for the State’s proposed energy supply plan.

The plant would be strategically located in Grange Castle Business Park, a hub for large manufacturing plants and data centres, and within the greater Dublin area where one-third of Ireland’s electricity demand is concentrated.

All the pieces appeared to be lining up, yet, according to Walshe, “with great regret” he and his business partner had no choice but to “pass on the baton and sell Grange to new owners” after years seeking to finance and build the plant as there was no obvious route to market at that time.

Despite planning permission, a grid connection offer and EPA licensing locked in by the time an auction took place in 2019, a missing piece meant that there was no viable route to market for Walsh. The major obstacle was the design of the capacity market.

Ireland's power grid is under pressure with record demand levels year-on-year

Ireland's power grid is under pressure with record demand levels year-on-year

Successful units are paid for each megawatt of capacity that they can provide when called upon to generate at periods of system stress. In theory, these payments should be enough to cover the fixed costs of the plant.

However, various letters, consultation submissions and presentations shared with our team show that, as early as 2014, Walshe consistently warned the CRU, EirGrid and the Department of Climate that this was simply not possible.

In order for a new build generator to raise project finance and materialise, it needs clear investment signals on price, duration and probability of winning contracts. “Otherwise, it is simply not possible to obtain financing,” Walshe said.

Two of the key concerns he raised were the price caps that he said were too low to support new builds, combined with the failure to have a strand for newly built plants separate from older plants that had undergone retrofitting works.

An artificially low auction price for new entrants, Walshe said, does not allow the developer to earn a reasonable return and “therefore the financial markets will reject” it.

The warnings were frequent and regular over the years, with Walshe and his partners outlining clear recommendations for separate auctions and longer contracts for new entrants and higher price caps.

The CRU told Noteworthy that the “current market design was the subject of a State Aid clearance process by the European Commission and is in line with EU requirements for such capacity mechanisms”.

Concerns ‘ignored and dismissed’

In a letter to the CRU and the Minister for Climate in November 2015, for example, Walshe warned that pitting new plants against existing plants with “inherent cost competitive advantages” would see new entrants “regulated to the bench”.

It beggars belief, the letter said, that there is “still such a disconnect” between authorities to “design a market auction that is fair, reasonable and equitable for all, including new entrants”.

Walshe stressed his continued “frustration” in a letter to the CRU’s chairperson in April 2016 that it was not budging on its concerns over the price cap and longer payment contracts for new entrants.

He also gave a presentation to the Department of Climate in February 2018. The presentation stated that even though the price cap is roughly 30% higher than for refurbished plants it would still be “impossible to win capacity contracts” for new entrants.

“The way the capacity auctions were structured, made it de facto impossible for new entrants to participate and benefited inefficient high-polluting large plants already on the market,” Walshe told us.

Yet, none of these concerns were taken on board and “were in fact ignored and dismissed”, Walshe said.

Grievances ‘across the industry’

Walshe was not alone, with UCC’s Paul Deane telling us that many of the concerns are “very valid grievances” that were raised “right across the industry”.

In a recent analysis, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) said that low auction clearing prices, at which successful bidders won capacity contracts, “may, in retrospect, have been unsustainably low” since the market’s inception.

According to Muireann Lynch, a senior research officer with the institute, a low clearing price is “not necessarily an issue in and of itself” as, in theory, it should provide a “very strong” signal for power providers to retire older plants, while also reducing the cost to the consumer.

However, Lynch said that “alarm bells” raised by certain players “have been borne out” to some extent, with no new plant coming online to date.

During a May 2018 consultation on the design of the auction scheme, other large industry players also expressed concern in relation to the methodology used to set price caps.

In its submission, the Electricity Association of Ireland (EAI), a representative body for some of the biggest players in the Irish electricity industry, said that underestimation “can have serious consequences for willingness to invest and for security of supply”.

The EAI’s concerns were still alive and kicking last December, when it told the Department and the CRU that its members consider the current situation “alarming”, “avoidable” and “a direct result of a regulatory approach that has failed to anticipate the growing signs of system shortage”.

Echoing the concerns raised by Richard Walshe, the letter stressed “deep frustration” with continued application of an “artificially low auction price cap despite clear market evidence and calls for review”.

Speaking to our team, the association’s CEO Dara Lynott said the principle of the market to get the greatest volume of electricity at the cheapest amount onto the system is “fundamentally fine” but is missing the signals to “get new plants onto the system”.

There needs to be a “clear trajectory” from the market design in terms of price caps to be able to go back and “give comfort to your investors that they’re not going to lose their shirts on this”.

Just enough capacity to meet peak demand

Another issue playing into investor confidence, according to Lynott, is the under-procurement of capacity. Authorities have “consistently erred” on the side of minimising the cost for the customer by procuring just enough capacity to meet peak demand, he said.

Cost to the consumer has played a big part in the design of the auction system. The average cost was €550 million in the previous scheme. By contrast, the first two auctions in 2017 and 2018 secured capacity to meet predicted demand for €333 million and €345 million respectively.

But, Lynott said, the potential failure to secure enough capacity on the system means the consumer will ultimately end up picking up the tab for emergency generation and the cost of other policy interventions. “The expense of that is way beyond a managed, procured well in advance kind of system… Under-procurement has been a consistent issue.”

A CRU-commissioned review of the auction system carried out by Ernst & Young (EY) earlier this year that found EirGrid had not “clearly signalled to the market the identification of a growing concern around a capacity deficit”.

EirGrid has publicly stated that it disagrees with “fundamental aspects of the report”. The State’s electricity operator stressed that the capacity system – designed by the CRU – is “not fit for purpose”, but stood over its own demand projections. This is backed up by a recent ESRI analysis that found peak demand levels since 2017 “have been broadly in line with those projected”.

Still, the ESRI’s Muireann Lynch told us that, due to the potential serious impacts from alerts and blackouts that can emerge out of capacity constraints, the authorities would “probably want to lean towards over- rather than under-procuring”. This is particularly warranted, she said, given the current make-up of Ireland’s licensing regimes where it can take years to get through planning.

“This means that we have to assume that at least some units won’t get through the red tape in time, in which case we need to over-procure at auction stage,” something she said, “we certainly didn’t do”.

Blockages and planning delays

Planning and regulatory constraints are another issue identified as not having been built into the capacity market system. Industry players, including Richard Walshe, have repeatedly argued consents should be a requirement for pre-qualification in the auction.

The lack of such a requirement, Walshe said, worked to the detriment of “shovel ready” new entrants with all consents in place, such as Grange.

Several successful projects have won capacity contracts but encountered challenges in the planning and regulatory systems and have not delivered in the roughly 3.5 year lead-in time for projects successful in auctions to get built.

As a result, the ESRI found that in the absence of robust mechanisms to ensure only credible bids gain contracts, “there may be an argument for raising the barrier to participation” such as pre-clearing planning and regulatory requirements.

According to the EY Review of the auction system, since the first auction was held, over 640MW of 2,500MW of new capacity that won contracts has subsequently been withdrawn. According to EirGrid’s latest capacity outlook, most new capacity expected to come online over the coming years has now been withdrawn.

Much of the shortfall relates to the failure of the ESB to build a number of projects in Dubin – two in North Wall and three in Ringsend, Poolbeg and Corduff. These had secured capacity in a 2019 auction and were supposed to make just over 400MW of power available for this coming winter.

When it bid in the auction, the ESB did not have planning permissions, grid connections or environmental permissions required in order to build such generation capacity.

The ESB has responded in length publicly refuting a “number of allegations” about its conduct in the capacity auction and released detailed internal reports, meeting minutes and update reports to Noteworthy outlining the efforts made to get the projects over the line.

At various stages, blockages and unforeseen delays in the planning and licensing process are outlined, with the ESB not satisfied that it was provided with a long enough extension to complete the project. The CRU told us that the extensions offered would give units close to completion the opportunity to meet requirements.

The 2022 EY review found that projects without consents that qualified for the auction were “unlikely to be deliverable” in the 3.5 year lead-in time.

According to UCC’s Paul Deane, trying to build anything in Ireland in a 3.5 year time period, even a house or a factory, is “incredibly demanding”, let alone for a power station. We need to look at “giving companies longer timelines to deliver on their capacity commitments”, he said.

In a letter to Minister Eamon Ryan in August 2021, the CRU outlined how auction participants had raised concerns that delivery periods allowed “may be too short” and that, while the auction may procure the capacity, the “key risks lie in the ability to deliver within the required timeline”.

Oil-fired Tarbert Power Station is due to close in the coming years

Oil-fired Tarbert Power Station is due to close in the coming years

Issues acknowledged ‘too little too late’

In the same letter, the CRU also recognised the wider concerns coming from industry, including that the clearing prices in the auction to ensure capacity for this winter “were too low to provide the necessary market signal” for some to enter the fray.

This in turn “acted as a disincentive” to participation in the next auction to ensure capacity for the end of 2024, leaving the regulator facing “the deficit from which we are now working to recover”, the letter stated.

The CRU told us that it is currently reviewing this and, early next year, “will make a decision on recommendations to take forward” from the EY report and industry feedback.

It added that, prior to the report’s release, it had already run a new auction and increased the price cap to “incentivise new capacity”, with further plans to review the cost of new entry that determines the level of the price caps.

It has now also directed the electricity and gas grid operators to give grid connection offers to plants successful in auctions and has a new monitoring regime for plants in development.

Recognition of the issues has been too slow, however, according to Richard Walshe. In a letter submitted to the EY review he said that, while the review was “welcomed as a constructive approach to attempting to address the structural failings” of the capacity market, it was coming “too little too late”.

Grange is under construction now under new ownership, but no other new plants have been built, meaning that there has been a failure to deliver efficient new power generation that EirGrid has factored into the future needs of a renewable-heavy system.

This also means that older, less-efficient plants are still needed on the system even though one of the aims of capacity markets is to provide incentives to replace or remove inefficient and expensive plants.

The Irish market was somewhat successful in this regard, with some of the heaviest emitting plants in Ireland failing to secure capacity contracts in early auctions, including one of the three coal-fired units at Moneypoint.

Today, almost one-third of our power is supplied by power stations that are over 30 years of age, half of which comes from units pushing closer to half a century in operation. As a result, unplanned outages and reduced generator availability is a problem, with issues flagged for several years now.

More frequent breakdowns and a lack of new builds means that older plants will need to stay on for longer, including Moneypoint that is now firing at full blast and fully contracted under a short-term capacity auction for this winter’s supply.

Retirements of plants ‘must be prevented’

Under the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED), some fossil fuel generation units that previously availed of a limited derogation (exemption) will be legally obliged to cease operation by the end of 2023.

Yet, security of supply is so bad at present that part of the solution being offered by authorities is to extend their lifetime. And the clock is ticking.

In its letter to Eamon Ryan last August, the CRU said that, given the precarity of the supply problems, EirGrid had advised that major exits from the market “must be prevented until such time as the deficit in capacity generation can be secured”.

“Given the shortfall from IED-related market exits that will arise in Winter 23/24, resolution of the above matters is considered a priority, secondary only to the securing of temporary emergency generation,” the CRU stressed.

Moneypoint Power Station is currently operating at full power in a bid to tackle the crisis

Moneypoint Power Station is currently operating at full power in a bid to tackle the crisis

On top of this, even if this derogation is achieved, many units are set to be excluded from the capacity market from October 2024, increasing the projected deficit for the following winter. This is because they will exceed new carbon intensity requirements from another EU rule – the Electricity Directive.

The CRU told Minister Ryan that it planned to engage with the units about the viability of running the plants for longer than anticipated and to work out “compensation required to provide the services needed” through a short, six-month capacity market for the winter of 2024/25.

While accepting that these proposals may be required now, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stressed to the CRU, EirGrid and the Department that the extension of the lifespan of these plants does not sit well with our requirement to limit emissions, and comply with strict national and EU laws.

Moving away from low-carbon future

Last autumn, when this idea was first floated, EirGrid contacted the EPA. Replying in October 2021, the EPA said that the options proposed “will move Ireland away from low carbon energy options” due to the proposed “prolonged or increased use” of coal, heavy oil and diesel-powered units.

When coal burning at Moneypoint decreased in 2019, there was an “immediate and dramatic impact on Ireland’s emissions”, with a 4% reduction in national emissions, the EPA said. Yet, the options now being considered, it warned, will reverse this positive trend and “impact on the State’s ability to meet the 51% emissions reduction target” in the Climate Act signed into law last year.

This is borne out by the numbers, according to UCC’s Paul Deane who has calculated that power generation emissions for 2022 to date are about 7% higher than what they were this time last year – “a terrible situation to be in for a country that puts itself forward as being the leader in clean, renewable power”.

The emissions spike is mainly down to the increased use of coal and oil units. If we had been successful in delivering new natural gas power plants, our emissions would instead be between 1% and 5% lower than last year, Deane calculated.

The Sustainable Energy Authority Of Ireland’s latest annual report, released last week, shows energy-related carbon emissions increased by 5.4% in 2021 due to an increase in energy use and the use of more carbon-intense fuels in electricity generation.

Similar to Deane’s calculations, the authority estimates that energy-related emissions will increase by a further 6% in 2022.

“If you don’t build new physical power plants in the system to complement the role of wind and solar, then you’re relying on what’s leftover – and what’s leftover is very old and unreliable plants. If these [were] horses, they would be put out to pasture,” said Deane.

“We shouldn’t be using them anymore. But we are, and not only are we using them a lot, but we’re relying on them,” Deane said. “And many people see that as a failure of the design of the capacity market mechanism to deliver”.

According to Deane, for now, we have to “deal with the world that we are living in rather than the world that we wished we lived in”. He added: “I wish we got the capacity markets sorted out, but we haven’t.

“This is a physical crisis of our own making.”

‘Heads must roll’

Once we get over this hill, the future may be a bit brighter, with progress this year on plans for both the North South Interconnector and the Celtic Interconnector - that combined will have the capacity to power up over 1 million households.

However, the earliest expected date the interconnectors will be up and running is 2026, with several winters in between to prepare for. The outlook until then is worrying, with the most recent auctions to get us safely through the winters of 2024 and 2025 failing to clear the new capacity needed for the Dublin region.

The Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications said that, “while margins will remain tight this winter,” there is a “large tranche” of temporary back-up generation being secured for the next three winters.

Despite confidence in turning the tide, Minister Eamon Ryan has initiated an independent review to identify how we ended up in the current scenario in a bid to avoid history repeating itself in coming years.

The Department said the final report was recently submitted and is currently being considered. To no surprise, Richard Walshe sent in a lengthy submission.

“The significant cost to Irish electricity consumers of all the auction failures should not be ignored and swept under the carpet,” he told us.

“Heads should roll.”

—

INVESTIGATING IRELAND’S ENERGY CRISIS - FULL SERIES OUT NOW

Part one reveals how staff shortages have left the energy regulator scrambling to keep the lights on. Part two examines how the growing energy needs of data centres are impacting on our climate targets.

Have a listen to The Explainer x Noteworthy podcast on our findings.

By Niall Sargent of Noteworthy

This investigation was part-funded by you, our readers. The remainder was funded by Uplift supporters to enable an in-depth examination of data centres.

Please support our work by submitting an idea, helping to fund a project or setting up a monthly contribution to our investigative fund HERE>>